Article by Nicole Gurgel (Albuquerque, NM); Photos by Melisa Cardona (New Orleans, LA)

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

— Audre Lorde

Throughout this year, I’ve been thinking a lot about these two words — decolonizing, aesthetics — separately at first, and now as useful companions to one another. As artists and cultural organizers committed to uprooting oppressions, living in a time of powerful protest against the violent, colonial legacy of this nation, I am starting to think about decolonizing aesthetics as foundational to our work in this world. Joining decolonizing to aesthetics transforms the latter into an action, it gives the word teeth, it anoints a vague and abstract term with revolutionary purpose.

In June, I attended a workshop at the Allied Media Conference led by the organizers of Akicita Teca, a Lakota youth program that works towards liberation through the recovery of traditional knowledge and language. There, I learned the Lakota words for decolonization: Ki wasicu etanhan ihduhdayapi. Word for word in English this means “to tear yourself away from the wasicu way;” wasicu refers to white / Western / colonizers, and translates literally as “the takers of the fat.” Having first encountered the term decolonization through abstract, academic language (while studying at a wasicu university), this visceral, direct definition breathes new life into my understanding of the concept. Decolonization is a forceful rupturing, a commitment to severing our connection to a system constructed to perpetuate inequity.

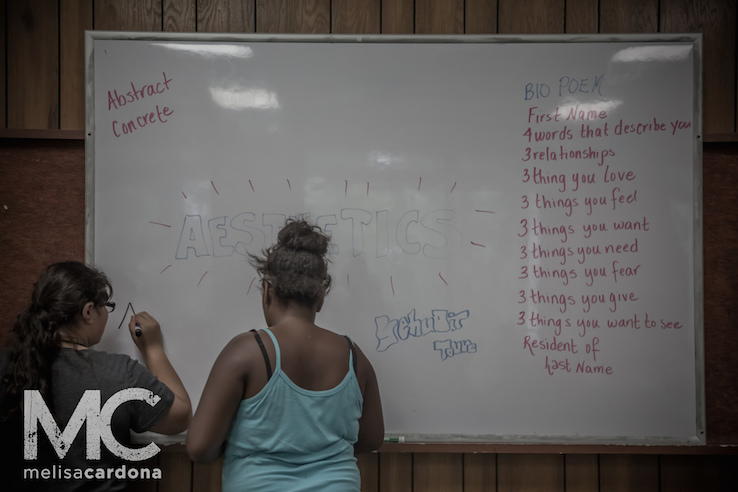

Since January, our ROOTS community has been collectively exploring aesthetics as an concept and as a practice. Many members have contributed their thoughts on the topic; you can find a growing list of these articles, dialogues, and videos on our blog. During ROOTS Week, Bob Leonard, Jan Cohen Cruz, Cristall Chanelle Truscott, Nick Slie, Linda Parris-Bailey, and Mark Kidd facilitated a Learning Exchange on aesthetics and documentation (for an overview click here, for the full transcript here) at which they offered this working definition of aesthetics:

“Aesthetics is an inquiry into how artists, in their products and processes, utilize sensory and emotional stimulation and experience to find and express meaning and orientation in the world and to deepen relationships amongst artists and their partners across differences.”

This definition positions aesthetics as an exploration of the tools artists use to commune and connect with audience-participants. It speaks to a desire to engage deeply and specifically about how and why we are making our work. It also speaks to our need to position aesthetics beyond its limiting, oppressive, Euro-centric legacy. In struggling for a better definition — a definition that honors the myriad cultures, histories, geographies, and styles present in the work of ROOTS members — we are laboring to decolonize this term. We are refusing to let our work be defined by supremacy; we are tearing ourselves away from hegemonic notions of beauty and artistic excellence. We are responding to Audre Lorde’s call that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Decolonizing aesthetics has been the process by which we reclaim a word often used against us, and redirect it toward our revolutionary visions.

The process of redefining this term is only part what I mean by decolonizing aesthetics. The other, more important connotation, is that we employ decolonizing aesthetics — aesthetics that decolonize. This second meaning identifies aesthetics as an action and an imperative. During the Learning Exchange, two panelists spoke to this. Cristall Chanelle Truscott of Progress Theatre asked us to consider that aesthetics is “less about what it looks like and more about what it does” and Nick Slie of Mondo Bizarro added: “Aesthetics is a verb, it’s a feeling, it’s an action.” As an action, aesthetics isn’t singular — it calls for a response. Or as Nick puts it: “It’s that I saw this, it made me feel … and then the big question is, well, what are we going to do about it?”

The work that Cristall and Nick’s ensembles create embodies the idea of aesthetics as an action, and one that inspires its audience to carry on that action. I’ve witnessed Progress Theatre’s The Burnin’ twice this year, and both times I felt the harmonies vibrate in my bones; both times I found myself singing the neospirtuals for weeks afterward. In Cry You One (which Mondo Bizarro co-produced with Art Spot), the audience is active for the duration of the performance. We trekked through the disappearing wetlands of Southeastern Louisiana, we danced, and sang, and, at the end, were invited to bow along with the cast. At one point, we were asked to mark our faces with dirt — to touch this disappearing land and carry it on our skin. Decolonizing Aesthetics are visceral, embodied, durational. They live with you; they require a different level of commitment from artist and audience; they leave us asking, “what are we going to do about it?”

_______

Nicole Gurgel is Alternate ROOTS Content Developer, as well as a writer, performance-maker, and educator living in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Nicole Gurgel is Alternate ROOTS Content Developer, as well as a writer, performance-maker, and educator living in Albuquerque, New Mexico.