The author, at center, with her parents, Mildred and Calvin Pevia. This article is part of the Creating Place project. View the full multimedia collection here.

By: Kim Pevia (Robeson County, NC) | April 25, 2018

Home: a place to be from…

Some of my earliest memories of “home” were when my dad would stop at this tract of land, lush and overgrown, in what felt like the middle of nowhere. He would make us walk with him as he would tell us about his vision of the house that he was going to build when he retired. He talked about each room – the living room, the kitchen, the bedroom, and a huge dining room where the whole family would gather for holidays and celebrations. He described the basement, the garden, and the barn where he would have horses, cows, and pigs. He was always wistful about coming back home. It seemed everything he did had an arc of bringing him back home.

In my culture everything is circular. Where you begin is where you end.

I learned early to walk in two worlds in many ways. One in particular was the life I had in Baltimore, juxtaposed against the life that we had when we came home – one very urban where I was a minority and one very rural where we were the majority.

There was never a question where we would be headed any time that there was free time away from work for mom and dad. We were headed home. Home was a 400 mile trek down 301 in the backseat of a station wagon. Home was Robeson County, NC, land of the Lumbee.

Arriving in NC was not only a physical homecoming but a spiritual homecoming. Coming to the land of my people, my ancestors, my history, my elders, my family gave me a sense of belonging that I have never felt anywhere else – at least not in the same way. Blood quickens at the sense of oneness with the land, with the river, and with the people. To be able to be among people who look like me, act like me, with shared histories and experiences.

Home: a place to take with…

The traditions of our food, art, and culture are woven into the fabric of who we are. There was a post WWII migration to Baltimore, Detroit, and other places where industry could afford a good wage and you could take care of a family. In order to make life livable in an urban environment away from the land, rivers, and people they loved, families took with them these traditions as pieces of a flame that stayed kindled until it reunites with the home fire. Much like the ashes we take from the ceremonial fire each quarter and bring them back to begin the fire for the new quarter, therefore the continuation of the fire, again all things coming full circle.

Gatherings matter. Community matters. They did then and they still do. Being away from home created a longing to gather with their own people, and was the impetus of my folks along with others to establish the Baltimore American Indian (Study) Center. They spent a lot of time and energy there. There was a drive to create a culture (a sense of place) there that was ours, so that we as young people would not be swallowed up by the dominant culture. It was so important for my sense of identity to be around and be informed by others who looked like me.

As an adult, no matter where I lived, the things that grounded me in each place were the things from home that I brought with me. It helped me maintain an even keel in a world that wasn’t familiar to me. Stewed tomatoes and rice in the winter, wherever I lived, was a staple of my diet. Chicken in a pot or chicken and rice or chicken and pastry smells are essential when I don’t feel well – bringing a sense of home to my stomach and to my spirit.

In 2017, the Lumbee were invited to participate in a two day celebration of our art and culture at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian called Lumbee Days. It was no coincidence that the things we took to display who we are, are the very same things found at the Artist Market and at Homecoming. It was a very proud moment to experience the sounds of our local singers and drummers filling the halls of the Smithsonian museum. The smell of collards and fry bread wafting the facility while I was talking with local artists, proud to be part of the experience, is one that I will never forget. It was a monumental opportunity to be on a national stage.

Home: a place to return to…

The longing to return usually resolved in an annual trek to Robeson County for Lumbee Homecoming.

Proud of our history, our art, and our culture, Lumbee Homecoming celebrates who we are and our ties to the land and to the Lumbee River. The official Lumbee Homecoming was started during the 4th of July holiday in 1968 and will celebrate its 50th year in 2018. It is estimated that 40,000 Lumbees from everywhere converge back to the land of our people. The annual event carries a tradition of food, song, nostalgia, and celebration of who we are, that we have survived in this place and on this land. While once held at the NC Indian Culture Center, it is now held on the streets of Pembroke, NC, where roads are closed as hundreds of vendors line the streets to sell jewelry, clothing, quilts, art, and every Lumbee food craving imaginable. The experience and triumph of the Lumbee spirit – “we are still here” – was such a boon to my spirit and to my sense of identity.

For decades the play Strike at the Wind was also enacted at the North Carolina Indian Cultural Center. It is the story of Henry Berry Lowry. Henry Berry Lowrie or “Henry Berry Lowry” (born c. 1844-1847; disappeared 1872) led an outlaw gang in North Carolina during and after the American Civil War. He and his men stood up to those who wished to enslave and to disallow the vote to the Indians of Robeson County. The play is performed and sung by Lumbee artists – men, women, and children, against a backdrop of nature and a hundred acre lake, reflecting a beautiful moon against a dark sky and dark water. His legendary story of resistance reminded us that we have the same courage – that we could also empower ourselves against those who seek to harm us. Songs written by Willie French Lowery filled the air. His most notable song was “Proud to be a Lumbee Indian.”

I have been home for 11 years now. It has been healing to garden, walk, pray, and dance on the land of my ancestors. Our culture feeds our souls. Part of my personal joy is being with the Elders quarterly at the Elder’s Ceremony, camping all weekend and hearing stories of our people around the social fire. Then the beauty of offering prayer inside the prayer circle around the sacred fire that has been maintained for generations on that same land, surrounded by hundreds of prayer ties filled with sacred herbs tied to the stakes and rails circling the fire, holding the prayers of those who made them and all those who have come to the circle. Tear streaked faces of those local and those who by happenstance learn of it from a local.

Home: a place to inform and preserve for seven generations….

Creative Placemaking, for me, is what we have always done. Our art and our culture grew out of the place from which we came and still inhabit. It came out of our need to self-identify and then express to others. It came from our collective talents and collective sufferings. And it continues to be part of our collective healing.

Although an incredibly sweet way of life, making a living here is not easy.

What does it take to stay on this land? What does it take to stay in this place where struggle is a real part of the day-to-day life?

There is beauty in the land here, and in the rivers and in the faces and the stories and the ways and the traditions and the culture with all is complexity. There is great value in the story of Strike at the Wind and other stories that beg to be told.

There is glory and practicality and sometimes literally medicine in the foods that we can grow here on the largest landmass in the state. Then the value added items that can come from those crops as well.

I came to understand that also woven into our making of home, is the thread of the soul wound of the historical trauma of the ancestors that has now been passed down to us. Hidden in plain sight in the outcomes of our lives, yet rarely addressed in that way, as the manifestations of the soul wounds.

While we were able to make home and to survive, we are still working on sovereignty as a way of life. How do we take sovereignty over our economies and create for ourselves an economy that is place based and creative and sustainable?

We are making strides, we started the Artist Market Pembroke in 2016 to give local artists a marketplace for their art. It has become a community gathering place, while providing a retail space that has elevated our pride in what we do. The market has a wide range of artists and products. It features fine artists who have been technically trained as well as cultural artists who learned from their parents and grandparents or other family member. It has also been a source of revenue for those who are returning to the community from both prison and drug treatment facilities. The art that is found in the Lumbee community is a meld of the old and the new. Woven baskets, corn husk dolls, wood carvings from cypress knees, homemade soaps and lotions and beadwork.

Also in 2016, we became aware of the very real threat of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline coming through our community. Three of the 20 high consequence areas designated in North Carolina are in Pembroke, home of the Lumbee. It has potential to impact the land and the river. As an act of resistance, the Lumbee elders circle, along with the Center for Community Action and a coalition of local folks called EcoRobeson, hosted a canoe trip down the Lumbee River on September 23, 2017 to bring awareness to what they are trying to do. Not only was it an act or resistance, but we were also able to receive the medicine from the river to continue the fight. For me, being on the river is healing and empowering. It was what I chose to do to celebrate my 60th birthday – to celebrate this river. The Lumbee River was an avenue of trade for my ancestors, not to mention food, sustenance, and recreation. I have distinct and clear memories of my parents and grandparents fishing in the river, boating on the river, swimming in the river, and holding baptism in the river.

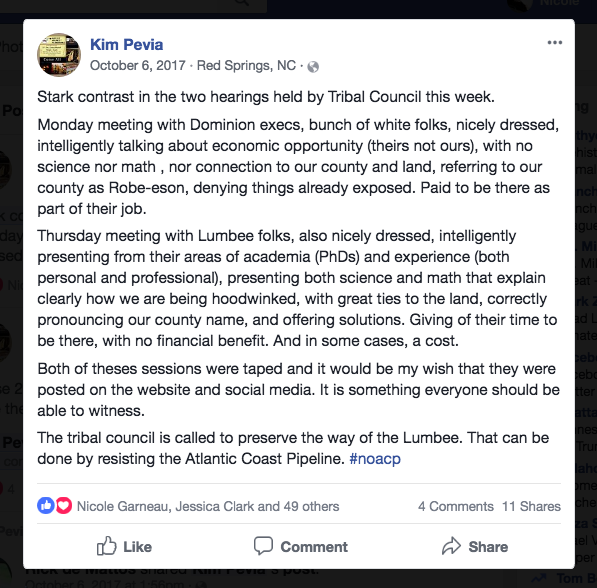

The attempt continues to take our land and our waterways. The beauty this time, is that we have highly skilled, highly educated, and highly articulate Lumbee who can speak to this issue. My Facebook post the night of the hearing was this:

Creative placemaking isn’t only making your place at home but creating home wherever you are. Then, figuring out a way to make it both sustainable and evolvable for seven generations. Creative placemaking for us has always been an essential way of life.

. . .

Kim Pevia is a seasoned practitioner of the human dynamic. Her work, guided by 30+ years of experience, invites us to an inner exploration. Specializing in emotional awareness that leads to emotional courage, for the last 12 years she has blended that work into issues of diversity, inclusion, and equity, providing a space and curriculum that allows folks of different backgrounds to understand and connect with each other. Her art is storytelling and reflection writing. She is a proud member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.

Kim Pevia is a seasoned practitioner of the human dynamic. Her work, guided by 30+ years of experience, invites us to an inner exploration. Specializing in emotional awareness that leads to emotional courage, for the last 12 years she has blended that work into issues of diversity, inclusion, and equity, providing a space and curriculum that allows folks of different backgrounds to understand and connect with each other. Her art is storytelling and reflection writing. She is a proud member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.