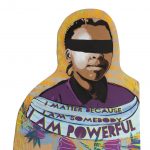

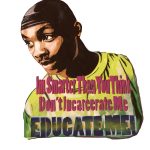

Justice Parade 2017, Performing Statistics. Photo: Craig Zirpolo. This article is part of the Creating Place project. View the full multimedia collection here.

By: Jeree Thomas (Richmond, VA) | April 25, 2018

“I am smarter than you think…

I am not a criminal

I am not an animal

I am powerful.”

On a hot and humid July day in Richmond, Virginia – walking distance from an old port that 200 years ago made Richmond one of the largest sources of enslaved Africans in the country – sat a group of primarily African American teenagers. For a few hours, three days a week during the summer, they traveled from their cells at the Richmond Juvenile Detention Center to ART 180’s Atlas Teen Center on Marshall Street.

They were a part of the second cohort of the Performing Statistics Project. One by one, they went into ART 180’s bathroom, which was rigged into a makeshift recording studio, and they spoke the words they had written. A poem called….I am Powerful.

Incarcerated youth are described as many things: juvenile delinquents, at-risk, bad, criminals. They are most dehumanized by those individuals who describe them only as a statistic and talk about their “rehabilitation” as a matter of dollars and cents. The purpose of the Performing Statistics Project is to hand over the power to describe and define themselves and what works for them and their communities back to teens who are directly impacted by the juvenile justice system.

If you define creative placemaking as individuals within a community using art and its resources to make their communities more livable and vibrant places, then youth incarceration is the antithesis of creative placemaking. It is taking one of the most valuable resources from a community, its children, and teaching them how to survive in an institution instead of how to contribute to a community. Hosting the Performing Statistics Project in Richmond was and is particularly significant, because black male and female youth who participate in the project are the descendents of a dark American legacy. They call the capital of the confederacy their home. They are surrounded by monuments, street signs, and buildings all paying homage to the individuals who once oppressed their ancestors.1 They, like their ancestors, are not free to live their lives independent of institutions that claim ownership and responsibility for them. Instead of using statistics to dehumanize, we were determined to use statistics to set the stage for their compelling narratives.

36.3% of children in Richmond live in poverty compared to the state’s average of approximately 15% of children. Richmond is one of the highest committing communities to the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) in the state of Virginia. In 2016, Richmond youth made up 11% of the youth committed to DJJ, while 71 other localities in the state had no commitments at all. In total, black youth make up 70.8% of the youth population going to the Department’s juvenile prisons even though they are only 20% of the child population in Virginia. Once incarcerated, the state spends approximately $171,000 to incarcerate one youth for one year, while only spending approximately $11,523 a year on their education.

In the words of Nell Bernstein in her book, Burning Down the House: The End of Juvenile Prisons, “The young people who rack up the million-dollar tabs behind bars, and the many more we spend hundreds of thousands to incarcerate, generally get the message: that they are at once disposable and dangerous – worth little to cultivate, but anything to contain.”

“Give me freedom

And I bet I’ll succeed…”

I became involved in the Performing Statistics Project when artists-activists Mark Strandquist and Trey Hartt reached out to the Legal Aid Justice Center’s JustChildren Program. At the time, I was a new attorney representing kids in Virginia’s juvenile prisons on their education, sentencing, and reentry needs. I regularly went behind the reams of barbed wire fencing to talk with my clients. Many of whom had been away from their families, their homes, and their communities for years. The weight of being their messengers, calling their mothers, sharing their stories, trying to push administrators, boards, and legislators to see what they were doing to children, was difficult. On many occasions, I wished that they could be set free to speak for themselves.

When Mark described what he wanted to do with Performing Statistics, it resonated with me. He wanted to amplify the voices of incarcerated youth, so that decision makers could hear from them. Their needs, their desires, their vision could be integrated into systemic changes. I would talk to Mark about the limitations of the law to protect the kids that I worked with, and who had the power to change those laws or policies, and those conversations became the outline for the project’s workshops.

What is unique about the Performing Statistics Project is that some of the earliest partners were system stakeholders, specifically the Richmond Police Chief Alfred Durham and the juvenile Court Service Unit in Richmond. The leaders of these systems worked with us because on some level they agreed with the premise that something was wrong with the system and while they worked every day to keep it functioning the way it’s required under the law, they wanted to hear from youth what could make it better and more effective for them.

It is not an easy task to discuss the mental and emotional wounds of systemic oppression. Many of the youth had been directly impacted by gun violence and police violence. Their fathers, brothers, uncles, and cousins were often topics of discussion. What they felt they had to do to support their family and uphold a certain image in the community were also topics of discussion. At their core, they did what they had to do for love, acceptance, and support.

The life-long effect of knowing death so intimately at such a young age has consequences. It colors the way young people think about themselves and their future. It makes negative stereotypes stick to them like glue, so much so, that even they start to believe them. Many of the youth in the project were told their entire life who they are not and what they can’t be, so we recognized it would take more than one summer for them to fully believe that they were powerful. Workshop after workshop, we would tell them how their words, their thoughts, their vision for what their community should look like to support them would be in the streets, at the General Assembly, and across the state. While they believed it, they still weren’t sure that it could make a difference.

“Believe that I am powerful.”

The Performing Statistics Project, specifically the work of each cohort of teens who have participated in the program have had a significant impact on both local and state policy. In October 2015, the materials that the teens created trained over 20 Richmond City police cadets. The same material would also train nearly a hundred the following year on what the police should know before approaching a teen. Their posters and screen printings would travel across the state and be prominently featured during state budget hearings in Richmond. The jail cell that they created with wood burn messages at the bottom of the cell would be the stage in which we would host a community forum with the Director of the Department of Juvenile Justice to answer questions posed by the teens and members of the community.

In 2016, the General Assembly allocated funding for more community-based programs for youth and in June 2017, one of the two remaining large juvenile prisons, which once held over 200 youth, closed.

The work of these teens was incredibly powerful, and their experiences inspired partnerships across the community. Television reporters, journalists, radio DJs, teachers, lawyers, activists, college students all came and continue to come together to amplify the words, work, and vision of the teens. Hundreds of years later, there is still a fight to reclaim the power, space, and voice of black and brown people in Richmond, Virginia, but this time there is a network of community members standing behind them.

“And I will become something one day.”

I am currently the Policy Director with the Campaign for Youth Justice in Washington, DC. The Campaign is a national initiative focused on removing youth under 18 from the adult criminal justice system. We work with families, youth, and state policy advocates across the country as they challenge laws that place youth in adult courts, jails, and prisons. I carry my work on Performing Statistics in my heart and into every new city that I work in. I’ve seen firsthand the power of creative placemaking and the importance of the people who live, grow, and die in communities being leaders and active participants in revitalizing and changing their communities for the better.

As a result, the Campaign for Youth Justice is emphasizing arts, advocacy, and activism in our policy change work. Every October, we host National Youth Justice Action Month. We support activities and events across the country that elevate the need for youth justice. This year our theme for the month is Arts, Advocacy, and Activism. We hope to encourage creativity and inspire thousands within their communities to think outside of a prison cell when considering how to rehabilitate their youth.

Most importantly, we wish to spread the message that youth are powerful and when given the space to share their experiences and contribute to shaping positive changes within their communities, they can dismantle entire systems and redefine solutions.

. . .

Jeree Thomas is the Policy Director at the Campaign for Youth Justice, a national initiative dedicated to the removal of youth from adult courts, jails, and prisons. Before joining the Campaign, Jeree was a Skadden Fellow and attorney with the Legal Aid Justice Center’s, JustChildren Program. Jeree represented youth in Virginia’s juvenile prisons and also served as the campaign manager of RISE (Re-Invest in Supportive Environments) for Youth, a statewide campaign to push for alternatives to youth incarceration. In 2016, Jeree was the inaugural recipient of the National Juvenile Justice Network’s Youth Justice Emerging Leader Award.

Jeree Thomas is the Policy Director at the Campaign for Youth Justice, a national initiative dedicated to the removal of youth from adult courts, jails, and prisons. Before joining the Campaign, Jeree was a Skadden Fellow and attorney with the Legal Aid Justice Center’s, JustChildren Program. Jeree represented youth in Virginia’s juvenile prisons and also served as the campaign manager of RISE (Re-Invest in Supportive Environments) for Youth, a statewide campaign to push for alternatives to youth incarceration. In 2016, Jeree was the inaugural recipient of the National Juvenile Justice Network’s Youth Justice Emerging Leader Award.

1 As of this writing, Virginia has 96 monuments dedicated to the Confederacy. The most confederate monuments in the country according to a 2016 study by the Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/20160421/whose-heritage-public-symbols-confederacy