A Keynote Address[1] by Andrea Assaf

Thank you, Alicia Burke, and thank you, Kathy Randels, for that wonderful introduction.

Hey, ROOTS Fam! Oh, my goodness…I am so honored to be entrusted with doing a keynote for Alternate ROOTS, and all of you. I’m also super nervous. For those of you are new to ROOTS – this is what happens when you don’t show up to a meeting.

[Audience laughter]

You get “VOLUNTOLD”—to do something important!

And so, I am very honored to be voluntold, to take on the challenge of trying to talk about race and representation. I say trying, because it’s a short period of time, and there’s so much we won’t get to. I entreat your patience, as we begin a conversation that might last beyond the space and time that we have right now, yeah?

[Audience Member: Yes, yes!]

My understanding of my charge, and what I’ve been voluntold to do, is to offer a way to talk about race and racism that is outside of, as Kathy said, the black/white binary. That was very much the way ROOTS talked when I, and many of us, came into the organization. So, this is hard and scary. It’s a challenge.

I also planned way too much, so I’m going to have to go fast, or skip stuff in some parts, because it is also very, very important that we take a moment before we break for lunch to honor John O’Neal, for which Stephanie McKee is going to lead us. And I wanna make sure that that has space.

I was also asked to mention, for those of you who are just coming into ROOTS Week, or haven’t been part of the longer conversations about UpROOTing Racism and all forms of oppression: the way ROOTS has been trying to take this on, in the last couple years, is to do a deep dive into a few topics each year. We know that means there’s a whole bunch of topics we’re not talking about, and it doesn’t mean we don’t want to or we’re not thinking about intersections. It just means that we can only do so much in our time together.

In this talk, I am going to speak from my own life experience and point of view as an Arab American person, and I know that might be challenging for some folks, if you don’t hear or feel your story reflected in what I’m offering. Let me just say to you that I have been a member of Alternate ROOTS for almost 20 years—next year I think it’ll be twenty—and to my knowledge, this is the first and only time we have ever, as a group, talked and thought about the Middle East. So I ask your patience.

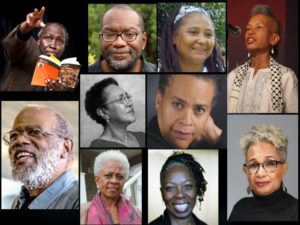

Before I begin, I want to lift up some folks without whom I would not be able to even have this conversation. These are African and African American elders and leaders who have poured into me their knowledge and wisdom and learning, who have offered me teaching and guidance, very often through this organization, Alternate ROOTS, and have mentored me.

By mentorship, I want to be clear that I mean, sat me down…

[Audience laughter]

…told me about myself, gave me a talking to, held my hand, challenged me, voluntold me to do something important, kicked me in the butt, made me walk through difficult moments. Mentorship ain’t always pretty. But the real stuff is what these teachers and leaders do. And I want to speak their names:

[From top left to bottom right:] Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Fred Moten, our very own Alice Lovelace, Miss Lucy Murphy, the dear John O’Neal, beloved Nayo Watkins, Linda Parris-Bailey (who’s in the room with us right now), Dr. Kimberly Richards and Jawole Zollar, through the Urban Bush Women Summer Leadership Institute (also, Stevie’s here too), and Ms. Keryl McCord, who we heard from on Wednesday.

[Audience cheers]

Yeah, please give it up for them!

[Audience applause]

I have learned from so many more people in this room—I’ve learned from many, many of you as colleagues—but specifically around having an analysis about race and racism, these elders took me under their wing and sat me down. When I was looking at this image, all together—Linda and I looked at it yesterday—and I had this moment of, damn, I am so lucky. We are all so lucky to be in the room with some of these folks. This is my honoring and thanks.

All right, so—what is this thing? What is race? I like to look things up, ‘cuz I’m kind of a geek, and, you know, I’m curious. What does mainstream culture say? Let’s find out. This is Googleable, from FreeDictionary.com:

race 1

(rās)

n.

5. Biology

adj.

What I was amazed to see is that, on the Internet, you can easily read what I was already gonna say.

[Audience laughter]

Number one: “A group of people identified as distinct from other groups because of supposed physical or genetic traits shared by the group. Most biologists and anthropologists do not recognize”—anymore—“race as a biologically valid classification.”

In part, because there’s more genetic variation within any one group than between groups.[2] So, that’s awesome. That’s the way it’s being put out on the Internet now… And there are other categorizations and details. My favorite one is the last one: “A distinguishing characteristic or quality, such as a flavor of wine.”

[laughter]

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we walked through the world this way, as if our racial classifications were like a flavor of wine? Delicious! And intoxicating!

[laughter]

But there’s also some really insidious things in this definition, like “a breed or strain for domestic animals,” right? When you think about the history of slavery in this country,[3] in the South particularly. That’s in there, too.

There’s also: “Humans as a group; the human race.” Could we get there? I know we’re not there yet, but could we get there?

You’ll hear some of us say sometimes—Ms. Keryl said it the other day—”Race is not real, but racism is.” I know for some folks, that’s immediately like, “Ouch! I live every day dealing with this thing called race, how can you say it’s not real?” What we mean by that is, biologically, scientifically, however you define it—race is not a “real” thing. It cannot be consistently defined. It is completely, socially, politically constructed, for specific uses of power and domination. That’s what we mean, “race is not real, but racism is.” Racism is totally real. Because it has been systematically, historically constructed for hundreds of years.

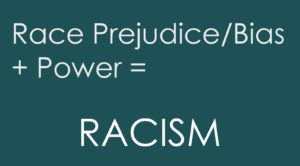

So then, what do we mean by racism?

Using the People’s Institute definition: “racial prejudice or bias, plus power, equals racism.” We started off the week talking about power. As Keryl said, you can use this formula to plug in and understand other systems of oppression. Such as, gender bias plus power equals sexism or transphobia. So, the power piece is really important.

Now, we usually talk about power here at ROOTS, and within this framework, as “legitimate systems sanctioned by the state.” You know, that’s things like Jim Crow laws, and slavery, and the Chinese Exclusion Act, immigrant detention and the Travel Ban, policing… Legitimate systems sanctioned by the state.

I’m going to say, “Yes, and…” Today, I want to talk about the power of representation, cultural representation, and stereotypes, and how that feeds into, and props up—in that fulcrum way that Keryl was talking about—these systems.

But first, some personal stuff. My mother and father: My mother is Beverly Ann Bell, and my father, Joseph Moses Assaf. My father was a Maronite Catholic, Lebanese American, also partly Sicilian. His mother was born in Palermo.

A side note about Sicily: If you go there, you will realize very quickly that it ain’t Europe. They consider themselves an island colony of Italy. And the folks are North African, Middle Eastern, Spanish, French, Italian, indigenous to the island—this incredible mix of histories, and millennia of conquest. They still consider themselves colonized by Italy, in the same way that many Puerto Ricans and Hawaiians consider themselves living under the colonization of the United States.

But anyway…When I say my father was Catholic, I want you to understand what a Lebanese Catholic is. His name was Joseph Moses. My grandfather’s name was Moses Joseph. His father’s name was Joseph Moses, and his father’s name was Moses Joseph, as far back as anyone knows.

[laughter]

I am serious! Those are Anglicized pronunciations, but you know, Catholic all the way back—since it was invented.

[laughter]

All right. So, my mother’s side was mostly Scottish and German descent (also Catholics), with maybe some English and Irish in there. That’s gotten a little more complicated since she did 23andMe, but basically…

[laughter]

I really don’t know much about my “white” family’s participation in genocide, colonization, or slavery, because I don’t know much about them before the Great Depression. There’s a rupture in my family’s knowledge of itself, because of class, misogyny, mental illness, institutionalization, and poverty. So, I’m not saying that lets anybody off the hook. I’m saying I just don’t know what that story is.

I think my father’s Lebanese family came here in the early 1900s to 1920s, when many people from Greater Syria and the Levant came to the United States—maybe fleeing the Ottoman Empire, or the French colonization of what is now Lebanon.[4]. I don’t have those details, either; except that it appears my great grandfather was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1921, when my grandfather was just three or four years old.[5]

What I do know is that, when my mother told her parents—her German, Scotch, English “white” American parents—that she was going to marry this guy, in 1971, they made “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” jokes, and refused to attend the wedding. (Yes, really.)

I was born in Norfolk, Virginia in 1973. A little historical background: Anti-miscegenation laws were still in the books in the U.S. until 1967. Those are the laws that prohibited races from inter-marrying or having kids. It was particularly targeted at African Americans, but you know, applied to inter-racial marriage in general. These laws go back to the 17th century. They were still on the books until six years before I was born.

But this is where it gets even more complicated. Were my mother and father different races?

[Audience Member: Aaahh…]

“Aaahh,” says Rasha Abulhadi! [laughs]

Legally, both of these people were considered white, on the books. According to the law of the time, they were not subject to miscegenation laws, because they were both legally white. But I ask you, if y’all saw this guy walking down the street, and you didn’t know he was Lebanese or Arab American, would you think he’s white?

[Audience Members: No…(various overlapping responses)]

What I want to say is that it really depends on who is looking. And where, and in what year. Right? Race isn’t real, but racism is.

Jennifer Chan, who was an editor of The Drama Review (TDR) in the ’90s, used to call me her “not-quite-white, not-quite-not-white friend,” because of these complexities.

Once, I asked Dr. Kimberly Richards to help me understand what she meant by internalized oppression, or internalized racism. She said, “What are you actually asking? Are you asking about internalized superiority, or internalized inferiority?” I was confused. I genuinely did not know how to answer the question. I said to her, “How could it not be both?” And she said, as she walked into a training, “You said that because you’re bi-racial.”

When I was six, my mother moved us from Washington, D.C. to rural Pennsylvania. This is the Appalachian Mountain range in Pennsylvania. Folks forget that even though it’s above the Mason Dixon Line, it’s still Appalachia. There, I was a racial enigma. “What are you?” was the question that sprang most often from the mouths of the curious and inappropriate.

There was no Arab American community, that wasn’t even language I had back then. I didn’t know what it meant to be “Middle Eastern” or “Arab.” I barely knew where Lebanon was, and had no idea why they were at war. I knew that when someone wanted to compliment my looks, they called me “exotic.” I knew that meant different.[6]

As a kid, I fought a lot. On the playground, after school. I fought because I got jumped all the time. I got jumped by white boys. I was a latch-key kid. My mother was a single mother working two jobs, and later just one job that took up her life, working at least until 5pm but often later. I had to walk myself home (from Elementary and Middle School). Sometimes, these boys were younger or smaller than me, but in groups. I got jumped for being a “Spic,” I got jumped for being a “Jew,” I got jumped for being an “Indian” (and honestly, I don’t think they knew what kind of Indian they even meant.) They did not know what I was—but they wanted to make sure I knew that I was not white.

I want folks to understand what living in this in between space is. Sometimes when I’m in the South, in a Black community, folks look at me and read me as white. And I get that. It’s, you know, it depends on who’s looking, and the context. But those kids in Pennsylvania wanted to make sure I knew I was not white.

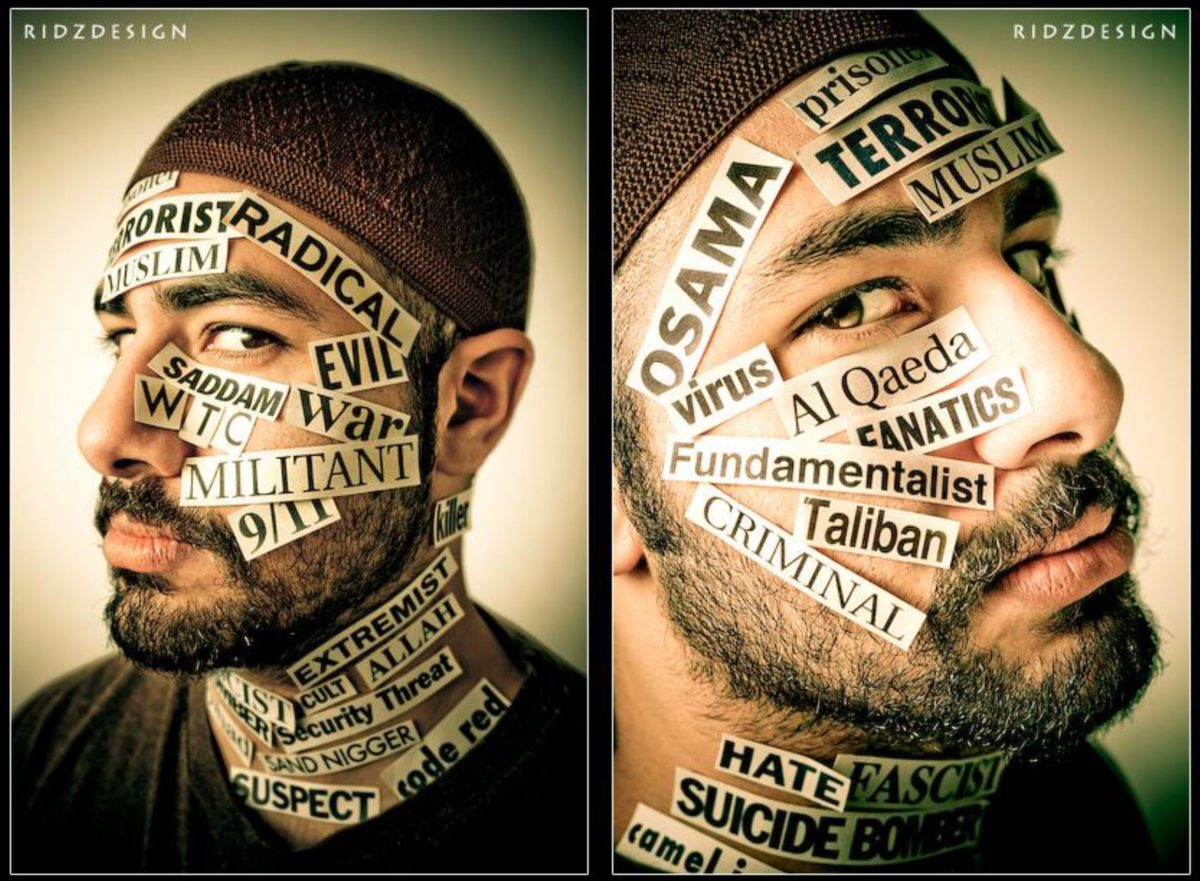

I’m going to show you some images. Because we’re talking about race, representation, and culture. So we’re gonna look at some stuff. We’re gonna look at racism. And I know this is hard. There’s one image from a painting that has some nudity, and there are some violent images from Hollywood movies. Like Dr. Kim likes to say, “Race is a sensitive topic, but this is not a sensitivity training.”

[laughter]

Just sayin’… So here are some images that I grew up with, in the 1970s.

For example: Ali Baba. There’s a million variations in movies, video games, TV, cartoons, picture books, you name it. But back in the day, they literally called him a dog.

Then there’s Hassan from Bugs Bunny. Bugs was my favorite cartoon. (I didn’t understand how racist it was then, I think I just liked that Bugs did drag.) Hassan’s only English word was “chop.”

Kim Pevia and I were recently talking about Ocean City, Maryland. We found out that we both used to go there for family holidays. This was the Fun House, until very recently. (People are all sad now that this racist thing got shut down.) This was the image of Aladdin. And what I want you to look at here is how images of anti-blackness—stereotypes of blackness from the ’20s or ’40s—are in this image, and then just overlaid with whatever they think the “exotic Middle East” is. Right? And what’s even stranger is you can see that the face is a different color than the body, because at some point they realized they couldn’t get away with that anymore. So they painted his body white. But his face is still the same! So this is what you get—this creepy, ridiculous mash up of anti-blackness, whiteness, India, Buddhism, Islam, and whatever the other mysterious “funhouse” image of the Middle East is, right? I grew up with this. Like, this was my family vacation, every year.

Oh, and of course, I Dream of Jeannie—which honestly was one of my favorite TV shows when I was a kid. [laughs] If you’re an Arab woman, this is what you get!

In case you don’t remember this, the premise of the show was: A U.S. Air Force captain crashes in the South Pacific, finds a bottle, rubs it, out of which a Persian, Farsi-speaking woman emerges. He frees her! And she kisses him!—falls in love, and follows him around granting wishes, and he becomes her Master. They literally used the word “master” throughout the entire 139 episodes.

There’s this ominous thing about exoticism: I had very long hair, down to my waist, until I was 20 years old. Being perceived as “exotic” enhances, you might say, the frequency with which older, adult male attention is paid… Adults, especially men, tended to consider the difference in my appearance attractive or sexy–conjuring, I suppose, fantasies of harems and submissive, yet magical women, with faces veiled and bellies exposed… And that exotification was dangerous—because it was sexualized. Older men were always reminding me that Beirut was so beautiful before the war—le Paris de l’Orient!—the Paris of the Middle East. And, “You’re gonna be so beautiful when you get older… How old are you?”

[Audience groans.]

Meanwhile, boys my own age, in middle school and high school, teased me horribly for being ugly. To the white kids in central Pennsylvania, my difference was not only unattractive, but abnormal. To them, I looked like a monkey–or more specifically, a baboon. They called me “Baboon” for nearly my entire eighth grade year.

[Audience Member: Oh my god…]

Yeah! ‘Cuz, you know, the ’80s…

I remember the moment when I began to understand what this contradiction of beauty and ugliness was all about. I was in twelfth grade, and I’d worn my glasses to school instead of contacts. I’m really near-sighted, so I had thick coke-bottle lenses at the time (the ones that make your eyes look smaller). A frizzy-haired and freckled red-headed girl in my homeroom class came up to me. “I like it when you wear your glasses,” she said, “they make you look more normal.” I got the point, even though she didn’t: “normal,” in this context, meant white – or, having more European features – which was clearly the standard of beauty that these young people were learning. It was a standard that I didn’t quite meet; and the “exotic” seemed to be a more mature, acquired taste of bedroom travelers.

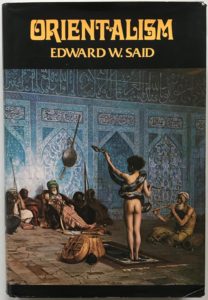

Orientalism, by Edward Said, was written and published in 1978. Said was a scholar, a writer, an activist and public intellectual, originally from Palestine. He died in 2003, during his tenure as a Professor of Literature at Columbia University. The theory of Orientalism changed—well, it gave us a way of talking about colonization and representation, culture and dehumanization.

The book cover is actually from an 1880 painting called “The Snake Charmer” by a French painter, Jean Léon Gérôme. There’s a lot happening in this image, right? Sexualization of a child. And these dualities: rich but primitive; religious, but to Europeans in the 1800s, totally scandalous; different shading of skin tones…right?

What Said was basically saying is that Orientalism is a form of racism and cultural superiority, a way that Europe, a.k.a. “the West,” imagined what is now called the “Middle East.” For a long time, it wasn’t called that. “Middle East” is a term actually popularized by the U.S.[7] Before that, it was just the Orient.

Through the repetition of this imaginary, these stereotypes that Europe invented about the people of “the Orient”—repeating it through science, and “experts,” and anthropologists, and journalists, and later movies and films, and newscasts, and literature, and paintings…By repeating, and repeating, and repeating, it becomes more real to Europeans and folks in the United States, than the people of the Middle East themselves. The belief in these stereotypes becomes more real than the actual people and places.

This is a strange person to quote, but Hitler used to always say, “If you repeat something often enough, people will believe it.” We see that playing out now, in our current political discourse, right?

So they took these people that are from regions as far away from each other as Morocco and Iran, over two continents, and called them a race—the “Orientals.” And then expanded that to include South Asia, and East Asia, all the way to the Pacific Islands!

The first time I cognitively remember having to fill out some kind of official form which asked my identity, I was in ninth grade. I looked at the form and stared at it in confusion. I didn’t see any option that really described me, and I didn’t want to check “other.” I looked at the options again, and tried to guess – as if it were a multiple choice exam, and I must be there somewhere, I just had to figure out which was the right answer. I knew I wasn’t really white, like my mother’s family; the Mary Kaye saleswoman who came to our house said that I had “olive” skin, and my older sister claimed that I turned green in the winter. I knew I wasn’t an American Indian (I think that’s what Native Americans were called then), even though I was sometimes mistaken for one. I knew I wasn’t black or African American, because my friends who were made it very clear that I was not… Then I thought about Asian: I knew that “oriental” rugs were from the Middle East, and that Asian people were sometimes called “Orientals.” I also thought that Indians from India looked kinda like me, and in some way I identified the most with them (my sister often teased me that I looked like the main character from The Jungle Book). So I called my teacher over, and asked her if I should check “Asian American.” She looked down at me and my paper, and wrinkled her face in disdain as she said loudly, “You’re not ASIAN! Are you?” I felt too humiliated and defeated to answer, so I simply checked the box marked “other”… It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and first read Edward Said’s Orientalism, that I began to realize—as a child in Pennsylvania, I had understood something experientially that the adults around me were not remotely conscious of, and had yet to comprehend.

Here’s an important quote from Edward Said: “As far as the US is concerned, it’s only a slight overstatement to say that Muslims and Arabs are essentially either oil suppliers or terrorists. And very little of the detail, the human density, the passions of Muslim or Arab life have entered the awareness of even those people whose profession it is to report on the Arab world. And what we have instead is a series of crude, essentialized caricatures of the Islamic world presented in such a way…”—and this is key—“as to make that world vulnerable to military aggression.”[8]

Here’s another thing I remember from my childhood:

Dehumanization. I’m going to show you a clip from this great documentary, Reel Bad Arabs.[9] They looked at over one thousand Hollywood movies, created over 100 years, and found less than 10 positive images of Arab or Muslim people. Less than one percent, over a century of Hollywood production.

CONTENT WARNING: Violent images from Hollywood films are included in this trailer.

Newsreel: It’s just like out of an action movie, but this is real. This is real! We are at war with Iraq…

Dr. Jack Shaheen: We are at war with Iraq. Wasn’t that easier because, for more than a century, we had been vilifying all things Arab? When we think of Arabs, what do we see? What images come to mind? Arabs are the most maligned group in the history of Hollywood. We’re portrayed, basically, as subhuman…If we feel that Arabs are not like us, are not like anyone else, then let’s kill them all. Then they deserve to die, right?…[montage of Hollywood film clips]…If we cannot see the Arab humanity, what’s left?

I encourage you to watch the whole documentary, it’s free online. You can buy it from the Media Center as well.

I’m going to skip over a few things here, for time, about how racism works in America. For example, how the N-word has been applied to Arabs, preceded by the word “Sand”…My first encounter with it was a very famous poem by that title by Lebanese American author Lawrence Joseph, written in the late 1970s…And my next encounter with it was online, post-9/11, how it exploded all over the internet. Also, Timothy McVeigh. If you look at what the news was saying first, in the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, before they found out (or told us) that it was Timothy McVeigh, they were all ready to say it was Middle Eastern terrorists. That’s all the first reports were, until Timothy’s face was on the news, and they had to walk back that narrative.

It’s definitely gotten worse since 9/11/2001. But I want you to know it didn’t begin with 9/11. This is a long, long, old history.

And the thing about living in this in-between space, between black and white, is that we get it from everybody. We have to deal with white supremacy all the time, and then sometimes we get it from other folks of color, too. An African American colleague once said, right it in front of me, to other colleagues, “Oh, she just got this job because the Arabs are the new POC.”

But being brown in America is not new—for any of us—regardless of what it says in the law about racial categorization.

You know, after 9/11, I was “randomly selected” five times in a row. How do you get, randomly selected five times consecutively? It’s statistically impossible. Wwe know that racial profiling is happening, even though we’re constantly told that it’s not happening.

It’s amazing how suddenly the winds of social consciousness and suspicion can change… how quickly you can find yourself in a chill, or a gust. How quickly imagination can get the better of you…

After 9/11, I felt like I went from being a total racial enigma, nobody knew what I was, to the next day, being an Arab—and not in a good way.

This artist, Wafaa Bilal, is Iraqi. He’s also a professor at NYU. He is an installation artist, and he did a piece called “Shoot an Iraqi.” He set himself up in a gallery with a paintball machine. People online or in the gallery could pull the trigger. He never imagined that 60,000 people would try to shoot him.

It’s much bigger than it looks on the surface.

If you can dehumanize people, it is easier to kill them. Or enslave them, or take their land, or lock them in cages, or deport them…It is easier for the state to impose those legitimized systems of oppression, if the targeted group of people have already been dehumanized.

And what do we do, Alternate ROOTS? We do representation. We do culture and images, narratives and stories. We paint pictures of people with our words. muthi reed said yesterday that we think we don’t have power, and we do. WE DO. We are the alternative media in this country. We are—artists, culture producers, people who have a microphone.

Even if we can’t change a law or a system, we can change the way people see a group that is being targeted, the way people see each other. We can do that together. We, ROOTS, could make a hashtag go viral in 15 minutes. I’m not even kidding. We just did this at the National Institute for Directing & Ensemble Creation, with far fewer people. If we organize ourselves and focus, even half an hour, on the same issue, we can have extraordinary impact. If we all decide that at every single cultural event that we do in 2020, we’re gonna have voter registration—and we live mostly in the South–think of the impact we could have.

We have so much power–not necessarily directly, in those legitimized systems and laws–but culture changes before policy. Culture changes before law. We are the ones who have to push the change. I know we all do that at home, in our communities, but I don’t think, honestly, that we do it together. So that’s my charge to us, before November 2020.

OK, I know we’re over time, and we wanna get to honoring John O’Neal… but before I go, I’ve got to tell you how Arabs became white in the United States. (You need to know this, I did some more research, and this blew my mind!)

So this Syrian guy, George Shishem, in 1909: He was from Zahlé (which is now in Lebanon, but at the time it was Syria). He immigrated to the United States. He was a police officer in Venice, California, and he tried to arrest a white guy. The white guy took him to court and said, “This man is not white. Therefore, he cannot be a citizen,” according to the laws of the time. “Therefore, he does not have the power or authority to arrest me!” So Shishem applied for naturalization, and tried to become a citizen, so that he could do his job as a police officer. And the naturalization court said, “Nope, sorry. You’re an Arab.” Remember those racial categorizations that Keryl told us about? Technically, he was a Mongoloid. That was the category for Asian at the time.

So he took up a collection. He got lots of money from the Syrian community, and he went to a higher court, and he fought to be considered white, to get that ruling, that historical ruling. He won. You know how he won?

[Audience Member: Jesus!]

Yes! I’m gettin’ there…Remember what Keryl said about the Doctrines of Discovery? “If they are not Christian, they are not human,” that’s what the Doctrines said in the 1400s. Shishem’s case rested on the fact that he was a Christian. (Remember that Joseph Moses, Moses Joseph, Joseph Moses thing?) He was a Christian, and he said to the court: “If I am a Mongoloid, then so was Jesus—because we come from the same land.”

And the court went, “Oh no, we can’t call Jesus a Mongoloid!” And they let him be white.

[Audience Member (Rasha): …So that he could be a police officer.]

Yes, so he could be a police officer. I know. It’s like a comedy, except this *ish ain’t funny!

I am wrapping up, but I just want you to know what my community is facing right now: Do we want a racial category on the census?

On one hand, yes, stand up and be counted! Votes matter, voting districts matter, policies based on the census absolutely matter to real people. On the other hand, under the Trump administration…

[Audience Member: Homeland Security watch list!]

Yeah, who the hell wants to check that box? I might as well sign myself up now, get surveillance cameras rush delivered to my home. (Free installation!) I might as well keep a packed bag marked “in case of interment” under my bed at night. Pride—in the midst of war—is still a challenge… Lots of folks still check “White,” if they can. And as long as that’s the political climate we live in, it will be difficult to get a clear sense of how many we actually are.

So I leave you with that conundrum, and I thank you so much for your time.

Andrea Assaf is a writer, performer, director and cultural organizer. The founding Artistic & Executive Director of Art2Action Inc., Andrea’s original work has been featured at Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF), La MaMa, The Apollo, The Kennedy Center, and internationally. Awards include: 2019 NEFA National Theatre Project, 2019 & 2011 NPN Creation Fund commissions, 2017 Freedom Plow Award Finalist, and 2010 Princess Grace Award for Directing. Andrea has a Master’s in Performance Studies from NYU. She serves on the Boards of the Consortium of Asian American Theatres & Artists (CAATA) and Alternate ROOTS, and is a member of RAWI, the Radius of Arab American Writers.

Endnotes:

[1] The following article is transcribed from Andrea Assaf’s live Keynote Speech at ROOTS Week, August 9, 2019 (filmed by Melisa Cardona). The transcription by CastingWords has been edited for readability, and expanded with additional text by Andrea Assaf.

[2] For an extraordinary expose on the construction of race, see National Geographics special edition, The Race Issue, April 2018: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2018/04/. Thanks to Keryl McCord and Equity Quotient for this reference.

[3] A significant element of the horrors of slavery in the United States included the forced sexual relations and procreation of enslaved Africans and African Americans. According to Wikipedia, “The objective was to increase the number of slaves without incurring the cost of purchase, and to fill labor shortages caused by the termination of the Atlantic Slave Trade” After 1808, there was a prohibition on the “importation of slaves” into the United States, and the internal slave market sharply increased. The politics, and corrupt moral logic of whiteness, on this issue were complicated; for example, President Thomas Jefferson supported the ban on the importation of slaves, but he also “owned” over 600 African American people, and kept extensive journals on “breeding.” For further reading, try Slave Breeding: Sex, Violence, and Memory in African American History by Gregory D. Smithers (University Press of Florida, 2012).

[4] The Ottoman Empire (from what is now Turkey), controlled much of Southeastern Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa between the 14th and 20th centuries. Under the Treaty of Sevres at the end of World War I, most Ottoman territories were divided between Britain, France, Greece and Russia. In 1920, the kingdom of Iraq fell under British colonization, and the French Mandate of Syria and Lebanon created new national borders for those countries. Lebanon remained under French rule until 1943.

[5] This sentence was added later. I actually discovered a record of my great grandfather’s naturalization certificate through internet research, about a month after the keynote address.

[6] Portions of this section are excerpted from “Coming Out Arab,” an essay by Andrea Assaf originally published, in part, in issue 16.2 of Mizna: Prose, Poetry & Art Exploring Arab America (Spring 2016). In the original keynote speech, parts of the essay were paraphrased.

[7] The term “Middle East” is thought to originate in the British India Office during the 1850s, to distinguish from the “Far East” which was considered East of India. However, it was Alfred Thayer Mahan, an American naval strategist, who instituted the use of the term, referring to the region between Arabia and India, in 1902. Later in the 20th century, in popular culture and common usage in the U.S., it generally refers to all Arabic-speaking countries, as well as Israel, Iran, some countries formerly in the Soviet Union, Afghanistan, and sometimes Turkey (which is part of the European Union). In other words, it’s a very vague, often shifting, political arena. In the 21st century, the term “MENA”for Middle East/North Africa has become more popular, although there is now a movement among cultural workers of “Middle Eastern” descent to more specifically name the region: North Africa, SouthWest and Central Asia.

[8] From the essay “Islam Through Western Eyes,” by Edward Said, published in the April 26, 1980, issue of The Nation. Available online as a special selection in The Nation’s Digital Archive.

[9] Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People is a documentary film directed by Sut Jhally and produced by Media Education Foundation in 2006. This film is an extension of the book of the same name by Jack Shaheen.