Article & Photos by Katina Parker (Durham, NC)

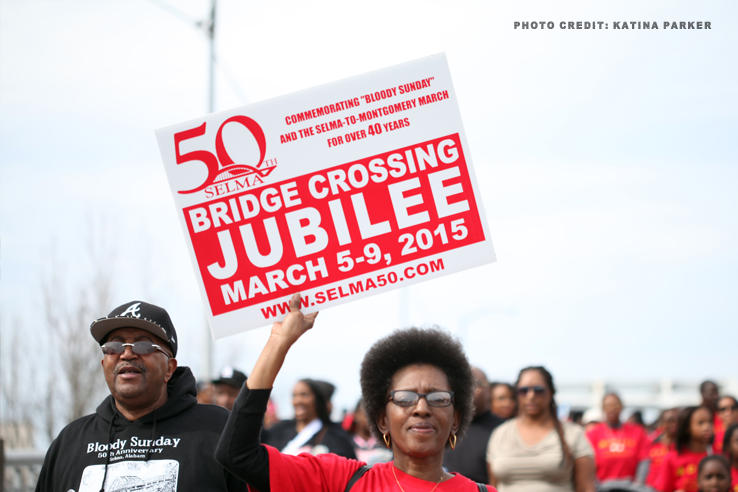

Saturday, March 7th. Selma, Alabama. Tens of thousands from around the world packed the streets leading to and from the Edmund Pettus Bridge to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, the Selma to Montgomery March, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Having never been to Alabama, it felt haunting, surreal, and unnerving, passing from Birmingham to Mobile, from Selma to Montgomery, connecting the geography marked by murders, violence, and blatant bigotry to the civil rights photography of Flip Schulke and Gordon Parks, which I’d spent much of my teenage years studying.

The hour-and-a-half trip from where I was staying in Birmingham to Selma was mostly winding road, and at night, just headlights, no street lights or cell phone signal to guide me back to the hotel. That Saturday eve, I was exhausted from a full day of shooting photos/video at the commemorative events. It had been hot, festive, and hard to move. The streets were so congested I missed most of my assignments, including President Obama’s speech. I did manage to hear North Carolina NAACP President William Barber II break down the present-day attack on the voting rights of poor people and people of color.

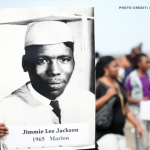

The drive gave me ample time to process many conflicting thoughts — the courage of the thousands who’d stood up against a type of tyranny that we now mostly recall through grainy black and white flashbacks. The strength of one woman in particular — Amelia Boynton, now 103, who earlier that day had posed for a photo with President Obama on the same bridge where fifty years before she was beaten unconscious by an Alabama State Trooper along with 600 other protesters who were en route to the capitol to demonstrate for voting rights. The photo of Mrs. Boynton’s 53-year old limp, bloodied body coupled with the murder of James Reeb, a White Unitarian Universalist minister from Boston, caused international outrage and pushed then President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

It was exciting that so many had come to mark the occasion and that the movie Selma along with nationwide protests against police brutality had likely increased turnout.

Alabama is one of the poorest states in the union. Hotels were overbooked. The narrow country lanes that doubled as highways were teeming with charter buses. Local entrepreneurs were hawking commemorative t-shirts as if they were at a sporting event. Gas stations ran out of fuel and water. Blacks, Whites, and Latinos were in the streets laughing and dancing together.

And yet something about it made me itch.

Years ago I would have attended an event like this with little critique for the celebratory tone, bountiful opportunism, or the VIP treatment reserved for elected officials and celebrities in attendance. But at 40, and after 6 months in Ferguson, much of it seemed incongruent with the difficult realities of today’s political climate.

The Voting Rights Act that we were there to honor had been gutted by the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013. States that were notorious for violating African American access to the polls via unjust taxes, physical threat, and other nefarious means are no longer required to pre-clear changes to voting laws with the federal government. Since then, several states have passed voter I.D. laws that will effectively prevent many African Americans, poor people, and immigrants from participating in elections.

As I drove, I thought about voting, something I do out of respect for my great grandmother, and due to my growing awareness that it must be valuable if White men in suits spend so much energy strategizing to exclude poor people and people of color. Think about it. The right to vote creates access to every other right granted to citizens, whether it’s the right to protest, the right to record police when they behave with excessive force, the right to an attorney should you be pulled over or arrested, the right to an equitable education, etc.

In this country, when you lose your vote, you lose the ability to improve your quality of life.

I don’t like the system of America. I don’t like anything that is intentionally set up to consume and distract us from our purpose, but there are reasons to vote, until we forge the new reality we’ve been working toward.

That’s what had me so conflicted, driving back and forth between Birmingham and Selma for Jubilee weekend, being one of those who’s committed to throwing myself upon the gears of a country that doesn’t value women, Black people, LGBTQ people, indigenous people, organizers, protesters, outliers, artists — all these cultures and communities that comprise my life; and at the same time being committed to carrying forth the legacy that my great grandmother and many of my elder family members risked their lives to establish on my behalf.

Sunday, Bloody Sunday. Half a century later. Thousands crossed over the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a confederate general who was also a member of the Ku Klux Klan. Among them, many of my protest friends from Ferguson. A triumphant moment. Yet bittersweet.

So many of us have risked our lives for freedom, and we still have so much further to go.

_______

Katina Parker is a filmmaker and photographer who teaches at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University. Her work focuses on African-American-led social protest and creating platforms for Black Queer people to tell the personal stories. Please follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Vimeo @katinaparker; and on Instagram @katinanparker.