By Edyka Chilomé (Dallas, TX) | May 30, 2017

“This land was Mexican once, was Indian always and is. And will be again.”

– Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands, 1987

I begin this article by acknowledging the place and time from which I write – January 2017. This week there is an itching in the consciousness of women all over Turtle Island (what is called United States of America). Many of us moving heavy, preparing our hearts in the ways we often do when we find ourselves sitting in the dark under a new moon. This week the world witnesses the crowning of a capitalist prince, an affirmation of an empire that has long reigned. This week in Dallas Tejas Atzlan brown women of all kinds will gather their many tongues with their children wrapped around their limbs and their uneven steps swirling around them like orbs. They will be armed with paintbrushes, poetry, stories, prayers, songs, chants, chisme, ganas, rabia – the weapons of resistance we have always known. We will gather in spaces that we have made safe with our hands and the tender fierce courage of our hearts. We will birth movement of spirit and minds in our homes, be that in our comadres’ living room, kitchen, or bedroom floor. We will tell each other of hermana Ofelia’s new space, The Meet Shop¹ in Mexican Oak Cliff where we heard she is hosting workshops for mujeres like us who have walked this land many more lifetimes then we could ever count. We will do this with a familiar urgency that we speak slowly and almost in whisper. We will do this as we readjust the bodies and spirits of our children wrapped around our waists. Their limbs and eyes learning what it feels like to be a colonized people creatively making place for survival again and again.

Creative placemaking is defined by the National Endowment for the Arts as “public, private, not-for-profit, and community sectors partnering to strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, tribe, city, or region around the arts and cultural activities.”² In my walk as an artist of color I have found that outside initiatives who feel the need to, “shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, tribe, city, or region around arts and cultural activities,” often intend to imply that these things are not already preexisting. More often than not, it is assumed by these initiatives that low-income communities of color are the spaces that are often lacking culture and art. Yet it seems particularly odd to assume that organized and intentional art and culture are not already present in a place inhabited by human beings. As we are a species proven to innately possess the impulse to create ritual of spirit and expression. This assumption implies, as in the tradition of white settler colonialism, that culture and human civility must be imported for the benefit of those identified as possessing less than human characteristics. Moreover, this assumption implies that in fact those who inhabit these communities are not themselves capable of and/or presently producing desirable art and culture without the outside assistance of private, not-for-profit, and or government sectors. It is of great significance that more often than not, these sectors and institutions are led and operated by white bodies who have inherited the historical class and cultural privilege of colonial powers.

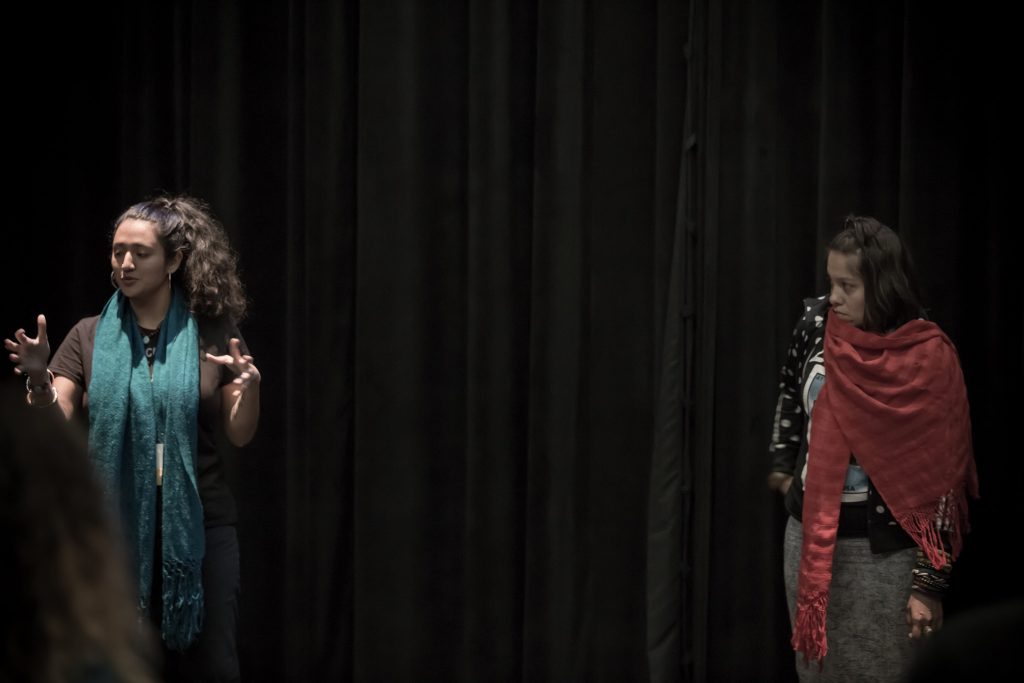

L-R: Edyka Chilomé and Liza Garza in When Earth Meets Sky, a workshop facilitated by Edyka & Vanessa Mercado Taylor at ROOTS Weekend-Dallas. Photo: Melisa Cardona.

As an indigenous mestiza Latina living in Texas, this patronizing and paternalistic colonial logic is far too familiar and common place in the reality of my people. We have historically been deemed unhuman, named by famous historians of Texas such as Walter Prescot Webb as stupid lazy children of vicious character or “people with blood of ditch water.” In present time we have been named by the now acting president of this country as rapists, criminals, and bodies to be murdered for past time. With laws like SB4, the latest racial profiling law passed in Texas, our lives, the lives of our families, and the livelihoods of our communities have been and continue to be controlled by a governing system that attempts to define our existence as legal or illegal. We are actively being punished and literally thrown into privately owned family concentration camps for existing on our own land that was stolen from us only a few generations ago. And when we are not actively persecuted, incarcerated, killed by the hands of (il)legal authorities, concepts such as “creative placemaking” or “revitalization” are imposed on our communities. These initiatives remind us that the perception of our humanity is dependent on the validation of outside forces. These forces promise to save us from ourselves by “strategically” providing us the opportunity to create culture and art as defined by white dominant culture. If you have not been made aware, Mexican people in the U.S. south are very much living a daily war waged against our humanity and existence. Art is no exception in the strategic weapons used against us – consciously or unconsciously.

The city of Dallas is a city that reflects the narrative of this country and the historical horror of the “wild west.” It is a city born of white settler colonialism and forced displacement. It is a city that is living the reality of historical and systemic apartheid. Mexicans and Mexican Americans along with other racialized immigrant communities are invisible in the dominant culture of the city though we have built this city with our hands. And we continue to build this city as it accommodates a non indigenous population while incarcerating and/or displacing historically looted communities to areas crippled and lethally laced in environmental racism. We are treated as a slave class, remnants of a conquest long won in the eyes of the cowboys, many of us slowly disappearing in the displacement of historical memory, cheering on the cowboys, told we must assimilate to survive.

The Oak Cliff Cultural Center’s gallery. The center is “dedicated to fostering the growth, development, and quality of multicultural arts within the City of Dallas.” Photo: Melisa Cardona.

Yet still, Dallas remains a city where indigenous mestizo peoples, survivors of war, continue to live resilience as a creative practice. As colonized peoples, our often unnamed practices of resilience have afforded us a spiritual, emotional, and physical pedagogy for community engagement. We honor our day-to-day experiences and stories as essential parts of our identities. Though we are seen as less than human in the eyes of the governing system and dominant white settler culture, our resilience ties us to alternate economies that are based on more than monetary transactions and goals. We are a people of enclave and family. A people of tribe and culture that tie us back to ancestral traditions that we actively honor daily in our relationships to each other and the land. Despite the constant reimagining of colonial forces, despite the ways in which capitalism attempts to dress itself as art, despite the constant strategizing of our displacement, imprisonment, and ultimate demise, we endure.

In the coming weeks, months, and years those who name themselves protectors of the air and the water will travel paths their ancestors have traveled all across Tejas Atzlan. They will stand on land that they remember, and that remembers them despite the thick blankets of concrete that continue to sever and displace our feet from ancient truths. Protectors, not protesters, will personify demands of the earth that have not been forgotten despite generations of war. We will stand in front of Energy Transfer Partners headquarters in North Dallas surrounded by white institutional wealth born of a capitalist empire and demand they remember their choice to desecrate sacred lands with illegal oil pipelines in the Dakotas and all over Turtle Island. With drums and spirit songs – with art we will reclaim place as we always have. We will make room to creatively honor truths that supersede the makings of urban planning or capitalist visions of an unsustainable future. We will speak prayers over our communities in our resilient barrios, in the streets of our hoods. We will demand young (and not so young) indigenous mestizx peoples remember they are meant to be more than the newest tokenized recruits for a non profit industrial complex. We will remind them that their identity is not dependent on a system that will exploit their labor as foot soldiers for the displacement and assimilation of their own people. We will remind them that the resilience of our people means more than violent western health care benefits and incessant resume building.

As in many of our ancestral customs, these creative and intentional acts of resistance and survival will be primarily led and supported by the women in the communities of Dallas and Tejas at large. These will be the women with full plates and responsibilities that the world expects of them and that their hearts demand of them. They will be underpaid, under supported, and overly worked in every sense of the word. They will be the shoulders that whole communities will rest on. Yet many of them suffer or will suffer debilitating and/or chronic illness. They will find heartbreak in every corner and reminders from a dominant system outside and inside of their own homes telling them that they are not worthy. They will be the ones we must hold space for and support in every and any way if we want to continue creating a life affirming world. Women will be the ones who must be prioritized in the strategic alliances made with outside forces who carry good intentions yet often times unnuanced gaze and unmindful understandings. Though survival as our primary creative practice is not easily marketable or exclusively created to be consumed by outside entities, it is a sacred practice. It is a practice that expresses the power of our own autonomy to resist in the face of severe oppression. It is a practice that must be respected and honored.

Our children, like us before them, are learning not to name resistance but to live it. They are learning to watch their mothers breathe it, to know that community, creativity, and our connection to the land is more than an edgy new theoretical concept clung to by white institutional paradigms of power. They will learn as we have learned that the life affirming spirit of a people who have remained rooted cannot be fabricated by theory or concept – no matter how well funded. We pray that our children continue to learn as we have learned that over 500 years of violent displacement and cannibalistic objectification, our root is tied to a creative spirit more ancient than that of language more enduring than that of city, more constant than that of war. We will make sure that our children learn to (re)(member) the parts of themselves that this empire, this city, would prefer remain fragmented, distorted, invisible, and forgotten. This is how we creatively make space for our survival and the survival of our world.

. . .

Edyka Chilomé is a literary artist, performer, educator, and cultural worker based in North Texas. She has published numerous articles, essays, and poems including a collection of poetry that explores queer mestizaje in the diaspora entitled She Speaks | Poetry, praised by Democracy Now en Español as “…a must read for those yearning to discover new ways to open up to deep personal and global transformation.” She currently serves as a faculty member at El Centro College in Dallas, Texas and was recently named top 25 most influential artists in the DFW by Artist Uprising Magazine. Learn more at Edykachilome.com.

¹ Since this article was written The Meet Shop, a community literary space owned by a Chicana resident originally from the Oak Cliff neighborhood, has been evicted and will be struggling to maintain the meaningful community and arts it has fostered in the neighborhood for the past year. Meanwhile bookstores exclusively owned and operated by and for newly settled white residents that fuel gentrification and displacement of residents of color in the northern part of Oak Cliff are flourishing.

² https://www.arts.gov/NEARTS/2012v3-arts-and-culture-core/defining-creative-placemaking