Genevia R. Turner in a Mississippi cotton field. Photo: Melisa Cardona. This article is part of the Creating Place project. View the full multimedia collection here.

By: Carlton Turner (Utica, MS) | April 25, 2018

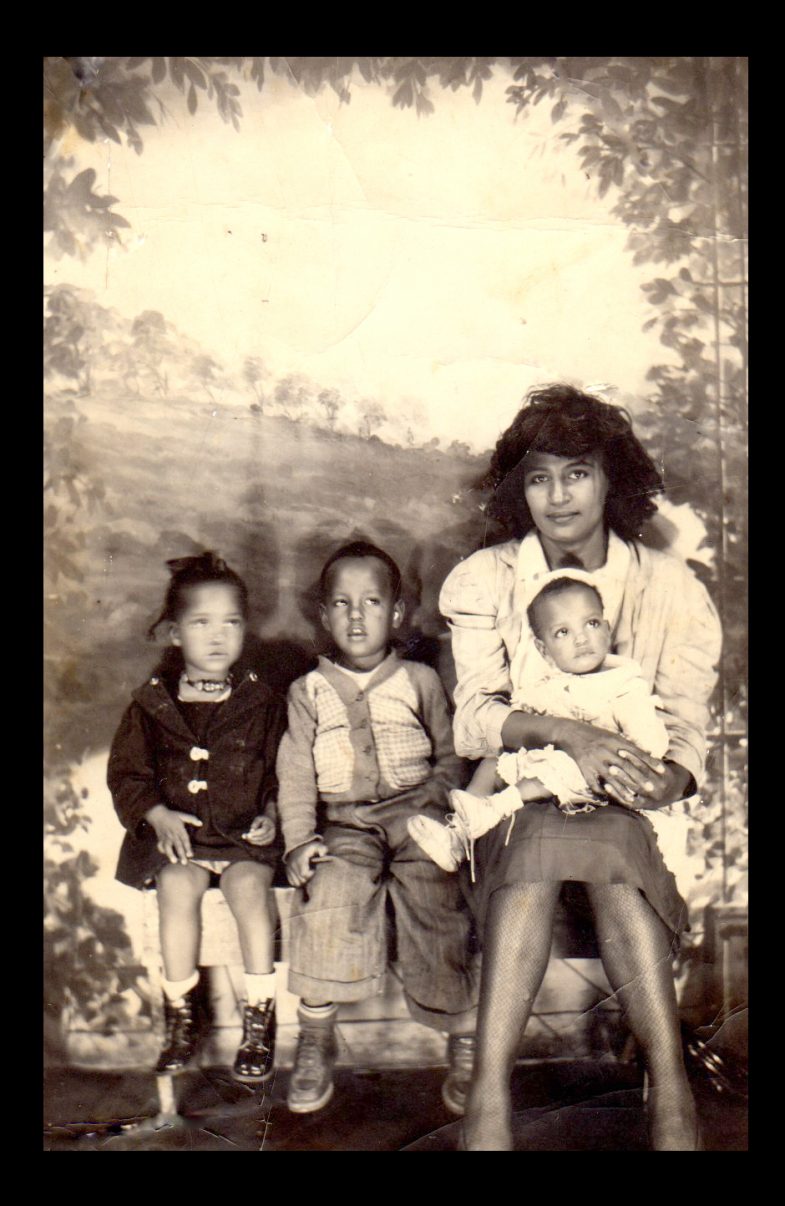

I grew up in Utica, Mississippi in a community with generations of historic memory, so I get to hear a lot of stories. Some of them personal, some funny, some tragic, some of them very, very, tall in their telling. All of them part of our history. These stories contain the collective identity of my community. I was also blessed in this tradition because my mother is one of many great tellers of story in my community. Two of her official roles are matriarch of our family and church historian. She can shift intonation, emotion, and voice to embody a character as only the best storytellers can. She has been the primary influences in the development of my own telling ability. If you have ever met her, then you have no doubt where I come from.

One of her signature stories, and she has many, goes back to her childhood and is the recollection of an actual experience. My mom was around five years old when she decided that she wanted to go to the field and chop cotton with her family. I won’t bother to tell you how difficult a task that is. You should already know and if you don’t that’s on you. My grandmother was adamant that my mom was too small and wasn’t ready. If you know my mother, then you know she doesn’t readily accept nos. Her grandfather, my great-grandfather, seeing her enthusiasm for work and her disappointment in her mother’s response, persuaded his daughter to allow her daughter to go to the field to work. So her grandfather sawed the handle of her full-size garden hoe in half so that she could better handle it in the field, and off she went to chop cotton.

I must have heard my mother tell this story a hundred times. And every time I heard it, it ignited a fire in my stomach and caused me to reflect on the injustice of the Jim Crow South and the lingering effects of chattel slavery on the bodies of little children of African descent. It wasn’t until last year, on the occasion of the 97th or 98th time I heard that story, that I asked my mom a question that I assumed I knew the answer to. I asked my mom, “who owned the land?” I assumed that she was going to speak one of the handful of white families whose names are etched on the road signs throughout our community, but to my surprise she gave an answer that shook my thirty year understanding of that telling.

“It belonged to us!”

In that moment, I was reminded of a tour my mother gave to Roberta Uno, when Roberta was senior program officer at the Ford Foundation. The tour consisted of me driving her and my mother throughout our community in my pickup truck while my mother gave a lesson in Black land ownership in the South. She told us about how Black men returned from World War I and spent their earnings on land. As we passed each pasture and parcel she spoke the names of Black families that lived in and owned those spaces. This was not a reality unique to our community, but an era of unprecedented Black land ownership. But what happened to all that Black ownership and the promise of self-determination and agency?

Well, in short, the forces of Jim Crow were so deeply ingrained in the markets, that Black farmers were excluded from monetizing the land they owned into generational wealth. The same land they had worked for generations as part of an enslaved workforce. The same land that generated generations of White wealth. Without access to the market, Black families were unable to afford to keep much of the land, and over the course of a few generations it was if the entire era had never occurred. Those large plots of land now display massive single family homes built by newcomers looking to escape the urban landscape and participate in country living. Black landowners were forced off of their land by discriminatory and predatory practices to make way for a community with different and sometimes opposing values. I wish I could say those days are gone.

Our communities were priced out of their land. If you can’t access the market in a market driven economic system, then the possibility of thriving is nil and the fundamental idea of survival is in peril. Today, in urban areas we call this gentrification. Some of that gentrification is fueled by developers looking to use creativity as the frontline of systemic change.

An Artist’s Response to Rural Gentrification

I write this piece as I am transitioning out of thirteen years as a staff member of Alternate ROOTS, an organization that has shaped and transformed the way that I see my work as an artist, an advocate, a human, and a manifester of dreams. At ROOTS I tried to practice organizational humanity. This idea rests in the art of shaping organizational culture and structures to fit the needs of the humans it serves, which is inversely different to bending our lives to serve a job. I am not always perfect in its practice, but the practice has endowed me with a keen sense of what is possible in reimagining the structures that govern our lives, beyond the workplace and into the living spaces we inhabit across our daily lives. I have found myself thinking about the ideas of creative placemaking and placekeeping every day in my directive to lend my time, energy, resources, network, and labor to harnessing the principles of organizational humanity into a space for civic engagement and leadership refinement. This is showing up in the physical universe in the development of the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production (MCCP).

The MCCP is a more than a project or an initiative. It is a directive to shift our community development framework from consumer to production. Consumerism happens when we are no longer connected to and/or responsible for the cycle of production of the goods we need to survive. The work of the MCCP focuses on the intersection of two particular needs of healthy human development – food and story, both assets found in abundance in our natural environment. This intersection has the ability to reimagine our relationship to the land, to agriculture, to food, to story, and to media production in an attempt to reconnect our history to the development of our present and future. The land is the source of our daily bread, and a symbiotic relationship with that land can yield a type of wealth and infrastructure that, although not unique to Mississippi, is steeped deep in the history of this place and these people, my people.

Through the MCCP we will focus on developing the communities’ ability to tell their stories and their histories through the medium of digital media (film, photography, and audio production), combined with a co-operative food production mission that encourages a culture of growing in a community that feels its ability to grow has been stunted by commercial agriculture and the industrialization of farming. And we mean growing literally. Our work encourages anyone that wants to grow to be able to grow. We are trying to impact the value proposition and equation the community has with its geography. We have been told for so long that our communities are poor and have little or nothing of value to offer, so our children grow up looking forward to the day when they get the opportunity to leave, many of them never looking back. Many people that used to live here have gone on to lead successful careers, their success being attributed to their departure from a place with very little opportunity.

I made a conscious decision to not leave my community. This place, where my mother’s stories originate and where my stories first found voice. I stayed because there is something important in living within a community and culture that holds its own in a way that is different and necessary for communities of color. It is important for my children to grow up with a clear understanding of what it means to be in and of a community. A community in which your achievements are celebrated, your failures given room to inform your growth, and your life is valued. I live here because this place feeds me in a way no other place is capable of. An additional gift of being a rural creative is the double dose of ingenuity and problem solving I inherited from my ancestors. My folks have the ability to see more than what is visible because our eyes are endowed with imagination and optimism.

Mississippi is both a state within the structure of the United States and a state of contradiction. A few of the important cross sections of contradictions driving the development of the MCCP are the presence of some of the most fertile soil in the country in the Mississippi Delta, access to this fertile land in abundance, and land that is affordable with a very long growing season. With this trifecta of fertile, abundant, affordable land we also have some of the nation’s worst health statistics in regards to hypertension, heart disease, obesity, diabetes, and infant mortality. Much of these disparities can be impacted by the culture we build around food, eating for comfort, convenience, and as an escape from the oppressive conditions that is everyday life in the rural South. Additionally, the stigma that comes with generations shaped by slavery, sharecropping, and Jim Crow endows each generation with a misconception on the true sense of wealth – land and its ability to produce and sustain life.

Agriculture is the foundation of community culture. Our celebrations, rituals, dances, songs, ceremonies, and relationships are informed by the seasons and the natural cycles and rhythms of the land. Our art is an expression of the symbiotic relationship we share with the land and the life it gives, the love we give the land and the life it gives us in return. The MCCP is eager to find out what this relationship looks like in this day and age, when given the space and resources to thrive.

ROOTS and PLACE

This compendium, Creating Place: The Art of Equitable Community Building, places the work of Southern artists in a context that stretches the framework of Creative Placemaking into a place that recognizes the practice of equity as a foundational principle of development. Within this publication ROOTS works to establish the many ways in which artists are supporting equitable development and shifting the ways communities are engaging in designing their futures.

The language of creative placemaking has generated a great deal of discourse at the national level. Since the inception of this concept – not the start of the practice – in 2010, the arts and culture sector has been trying to figure out how to navigate this space in a way that offers buy-in by those with capital and physical resources while keeping the language of creativity and community on the table. To place arts and culture at the center of city planning and urban reimagining. Initially this concept was focused on art and culture as the focal point of aesthetic design, form and functionality, focusing city revitalization efforts in the form of cultural districts across the landscape. The goal was revitalization through community economic and social development with art as product and vibrancy being a central indicator of community health and economic vitality. The intent was to encourage public/private partnerships by engaging civic leaders, developers, designers, and artists in a collective conversation about function, purpose, and the aesthetics of place.

In many ways Creative Placemaking as an artistic genre and community development approach has changed the landscape of both art and community development. Legitimizing and normalizing the role of artists, designers, and culture bearers in the community development, policy, and urban planning spaces. It has altered much of philanthropy, breaking internal silos and creating a bridge for arts programs to integrate or partner with more traditional community development programs. Pooling resources to make resources available to create a wider impact on community development than just arts programming, production, and presentation. This work has been instrumental in bringing artists to inform policy in transportation, housing, public works, environment, and main street commerce and aesthetics.

The investment in this idea has been significant. In my opinion, it has altered the very landscape of philanthropy, shifting foundation portfolios specifically directed to organizations and individual artists into Creative Placemaking, a program which offers philanthropy the opportunity to integrate more of its internal programming to support a broader sense of community development. And, as with most new funding initiatives, this new investment and interest in the intersection of art, design, and the physical infrastructure aspects of community development brought with it a shift in the way artists saw themselves in the funding ecosystem.

In 2011, ArtPlace America launched a ten-year initiative backed by thirteen national and regional foundations and six of the nation’s largest banks in an attempt to solidify creative placemaking as more than a passing fad, but a best practice in community revitalization and development and create a place at the table for artists and arts organizations to have a seat at the development table.

My work at Alternate ROOTS has granted me a particular type of access to spaces considered early adopters of the new language of philanthropy. I probably first heard the term Creative Placemaking at a foundation meeting or at a conference like Grantmakers in the Arts. These spaces are the launching pads for field-wide initiatives. As with any new language, there were hot, cold, and lukewarm responses to this new directive. Most of all, grantors and grantseekers, wanted to understand what this new language meant in terms of their portfolios and to the opportunities for funding. They wanted to know how this new direction would impact the flow of funding. What did this language mean, how does it impact our organization, giving, how much money is involved, and what are the long-term implications of this new way of thinking about artists working in community? ArtPlace has been a force majeure on the arts community. It has leveraged this concept of creative placemaking into a national conversation about place, belonging, and the role of artists in community development. In a time when philanthropy is going through leadership transitions and the inevitable winds that shift in the wake of this movement, ArtPlace and the creative placemaking movement has created clear and effective ways of validating the voice of artists in sectors that have rarely seen artists as more than products to be produced, presented, and consumed. What does it mean for artists to be in positions to inform decision about the design of their communities?

Can we normalize holistic cultural practices into formalizing the way that organizations, institutions, and communities think about their role in community development? Can artists working with an equity framework counter the effects of the weaponization of artists as frontline gentrifiers? How do we learn from the history of this work through projects like the American Festival Project and Freedom Summer and acknowledge their legitimacy in a creative placemaking frame?

My work at Alternate ROOTS afforded me the opportunity to be in many conversations concerning national cultural policy. Most of those conversations regarding the creative placemaking directive focus on the building out of physical infrastructure and its ability to drive economic growth and impact development. What is usually absent from these conversations is understanding how artists impact the quality of life in a place and the culture that shapes that place. This is where Alternate ROOTS can claim space. This is why this project is so important. For forty-one years Alternate ROOTS’ artists have been working at the intersection of arts and social justice to inform the creation of just and equitable communities. This is the most important component of community development, yet the most under-resourced and supported. We hope the work of this publication can provide additional space for this conversation to inform and refine our collective practices and invigorate more people to engage in this form of equitable development. But more than hope we will continue to work towards being a model of the change we want to see in the world.

If you are ever in central Mississippi, please come by and sit on our porch and share a fresh meal and some stories. There are more than enough to share.

. . .

Carlton Turner works across the country as a performing artist, arts advocate, policy shaper, lecturer, consultant, and facilitator. He is founder of the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production, which uses arts and agriculture to support cultural, economic, and social development in his community of Utica, Mississippi where he lives with his wife Brandi and three children. Carlton is a 2017-18 Ford Foundation Art of Change Fellow, a Cultural Policy Fellow at the Creative Placemaking Institute at Arizona State University, and a member of the Rural Wealth Lab at RUPRI (Rural Policy Research Institute).

Carlton Turner works across the country as a performing artist, arts advocate, policy shaper, lecturer, consultant, and facilitator. He is founder of the Mississippi Center for Cultural Production, which uses arts and agriculture to support cultural, economic, and social development in his community of Utica, Mississippi where he lives with his wife Brandi and three children. Carlton is a 2017-18 Ford Foundation Art of Change Fellow, a Cultural Policy Fellow at the Creative Placemaking Institute at Arizona State University, and a member of the Rural Wealth Lab at RUPRI (Rural Policy Research Institute).