By Andrea Assaf (Tampa, FL)

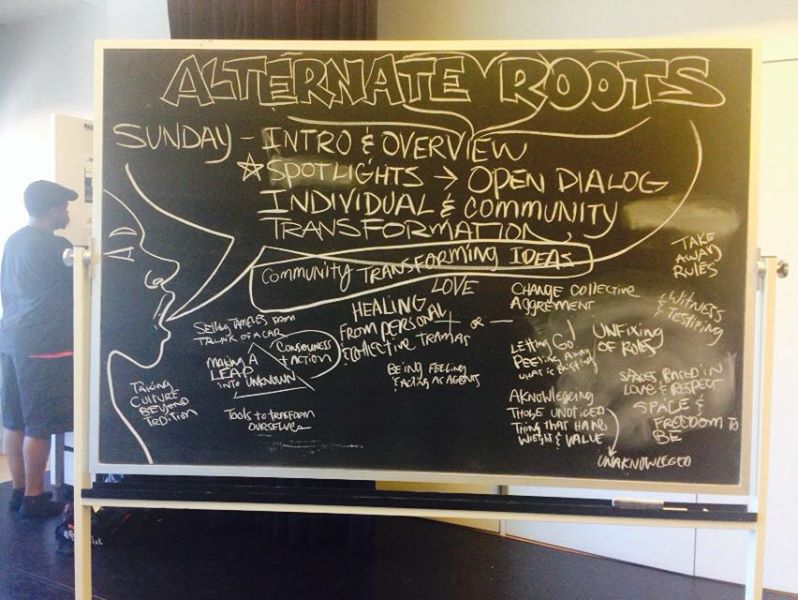

Setting the Stage: Alternate ROOTS Workshop on Principles of Community Engagement

At the Hemispheric Institute’s 2014 Encuentro in Montreal, I participated as a member of the Alternate ROOTS co-facilitation team leading a five day workshop focused on the Resources for Social Change (RSC) Principles of Community Engagement: Open Dialogue, Shared Power, Partnership, Aesthetics of Transparent Process, and Individual and Community Transformation.

Each day featured a different Principle, or practice-based approach to embodying these principles. In our daily 9-11 AM workshop time, we were able to create a mini-ROOTS environment of creative exploration, mutual support, and community building.

On the first day, demonstrating one of our core facilitation practices, we collectively created group agreements for our time together. When the term “safe space” was suggested, Baraka de Soleil raised a concern that the notion of “safety” is sometimes used to silence anger or strong emotion (especially if expressed by people of color in response to racism), or to impose a political correctness that is not genuine nor productive. This led to a discussion of what “safe space” means in the context of community organizing or artistic process that is dedicated to progressive social change, and meaningful transformation.

We clarified, together, that a “safe” space is not a censored, stifled or policed one. A safe space is one in which individuals take responsibility for their words and actions, as well as for their own bodies and feelings; where not only the facilitator, but everyone has a responsibility to be conscious of the power dynamics in the space, how those dynamics either reinforce or counteract historical systems of power and oppression, and which dynamic one is contributing to at any given time. A space is “safe” when enough trust has been built, intentionally, among participants and facilitators, that difficult discussions can be engaged, and strong emotions can be expressed, in service of the shared goal of increasing understanding and uprooting the internalized -isms and phobias that are buried deep within all of us. A safe space is not immune to mistakes or missteps, or even offensive statements or gestures; but it is one in which participants are collectively capable of, and committed to, acknowledging and addressing them in an ethical and caring manner as they arise. In other words, a safe space is one in which it is possible to challenge each other with love, to rub up against our growing edges, to express pain and apologize when necessary, and to hold each other accountable. This shared understanding of what we, in the ROOTS workshop, meant by “safe space” proved to be an important tool as the Encuentro progressed.

The Principle of Community Engagement that I was assigned to focus on was Open Dialogue. I decided to begin by exploring the distinction between debate and dialogue. Through a collective brainstorm, we articulated some key characteristics, and the ways in which cultural organizing or collaborative creation approaches may be different from what is normalized within the academy, or even promoted by systems of academic discourse. For example, the ROOTS Principles state that “Active listening and honest response is imperative for open dialogue. We base our work in exchanges in which experience, questions, dialogue, and reflection, rather than lectures or a top-down approach, are used for sharing and giving information.” Drawing from my background with Animating Democracy, and the multitude of dialogue facilitation specialists who informed that work, we discussed and responded to some of these basic comparisons:

[full][half flow=”start”]

Debate

- Combative

- Attempts to prove the other wrong

- Assumes there is a correct answer, theory, method or truth

- Listens for flaws or counterarguments

- Critiques the other’s position

- Defends assumptions as truth

- Searches for weakness in opponent’s argument

- Seeks a conclusion that ratifies one’s original position

[/half][half flow=”end”]

Dialogue

- Collaborative

- Attempts to achieve shared understanding

- Assumes multiple people hold multiple truths, and that solutions may be found together

- Listens for meaning and areas of agreement

- Suspends judgment to listen for understanding

- Reveals and questions assumptions

- Searches for value in others’ positions

- Discovers new options, and seeks a shared conclusion that benefits all

[/half][/full]

These differences of approach to communication became visible as the week unfolded, not particularly within the creative time-space of the ROOTS Workshop, but as issues arose throughout the course of the Encuentro. The Hemispheric Institute, which grew out of the academy (New York University’s Performance Studies Department, specifically), holds academic discourse as a value, which is generally driven by a debate model that plays out in publications, as well as in how academics and theorists are trained to engage in classroom discussions (and by extension, conferences). Alternate ROOTS, however, holds dialogue as a value, and has spent decades developing some of the most skillful facilitators, and practices, in the cultural field. As someone who was educated at NYU, and introduced to theory in the Performance Studies department, then mentored for over a decade after by Alternate ROOTS — it became clear to me how some of the values that underlie ROOTS practices could be useful to the Hemi community. Such values aren’t necessarily written, or explicit in the ROOTS Principles of Community Engagement, nor official organizational values; but they are living practices of ROOTS artists and cultural workers — the bearers and builders of the Principles — who have influenced me over the years.

In this article, I will share observations and reflections on some of the key issues that arose, and the “interventions” (as they were called at the Encuentro) that they sparked. I am interested here in reflecting on how ROOTS team members engaged, and how these living values we’ve learned through ROOTS showed up, particularly when conflicts or challenges arose. As The Hemispheric Institute and Alternate ROOTS continue to develop exchanges and partnership, these reflections are offered in the spirit of dialogue — or dialogism, in the Bakhtin sense of extending in both directions, continually informing previous and future work. In some way, this growing relationship may be explored like the dynamic tensions between theory and practice, each having gifts to offer the other.

If you’re interested in reading more about the experiences of other Alternate ROOTS Workshop Co-facilitators at the Encuentro, please also visit the blog posts of Ariston Jacks, Ebony Noelle Golden, Keryl McCord, and Nicole Garneau.

Intervention 1: Supporting Accessibility, Holding Space & The Open Non-Mic

As part of the Encuentro, the Hemispheric Institute had organized several working groups. The “Performing Disability / Enabling Performance” Working Group happened to meet right after the ROOTS workshop each day, in the same studio. A couple of the working group members also participated in our workshop. One of the issues that quickly became clear at the Encuentro was the lack of accessibility of some spaces where Hemi events were taking place in Montreal. For example, La Sala Rossa, where the late-night “Transnocheo” performances and DJ party regularly took place, was two flights up, with no elevator. On the second night, the Working Group staged an intervention, spread through social media as #IamChair.

This intervention is best described by Encuentro participant and Montreal-based artist, Jordan Arseneault, who posted the following on Facebook:

“Last night I saw the most powerful demonstration I have ever seen in my life. At least three people who use wheelchairs hoisted themselves on their bare hands up the stairs of La Sala Rossa to draw attention to the inaccessible nature of this venue as a site of art-making for Hemispheric Institute Encuentros. I will never be the same. Afterwards, there was an ‘Open Non-Mic’ in front of the venue with-and-for those who could not access the space … Después de que muchas personas entraban el lugar del Trasnocheo, pasando por encima l@s manifestantes literalmente, tuvieron un espectáculo abierto en la calle para mostrar nuestra solidaridad. Esta mañana lloré.” (Translation: “After many people entered into the place of the Transnocheo, passing over the protestors literally, they had an open show in the street to demonstrate our solidarity. This morning, I cried.”)

When Alternate ROOTS team members arrived at the site, and saw the action that the Working Group had staged, we knew we had to respond in solidarity. After all the years that Alternate ROOTS has struggled with issues of accessibility — and continues to face our own challenges as an organization and a community in this area, even as we are committed to collective accessibility as a value — it was immediately clear that this was a moment ROOTS needed to show up for. It was a moment that challenged me to ask myself what it meant to be an ally, not only in theory but in action.

My first choice was not to go up those stairs. Some of our colleagues were not able to enter, or chose not to under the circumstances (there was a deep and complex discussion about personal dignity and choosing not to be carried in), so some of us decided to give up the privilege of access that night. Once we were gathered there, on the street, the question became what to do next …

Well, ROOTers know how to do late-night, now don’t we! I suggested we start an Open Mic (which came to be called the “Open Non-Mic” since we had no equipment). Guillermo Gomez-Peña, who was scheduled to perform upstairs, announced “Los Dos Transnocheos!” Baraka de Soleil called out, “Who wants to throw down?” We nominated D’Lo as our emcee, and circulated a sign-up list. Nicole Garneau just happened to have her prop and costume in her bag (yes, she travels with tools), and was asking if public breast-bearing might be cause for arrest in Montreal (which it’s not). Soon volunteers were taking donations for a snack table, and running drink orders upstairs. And something beautiful happened, right there on the street …

After the action, I had my own learning moment about how to be an ally. I was very moved by the experience, and suggested that we continue to stage an alternative Transnocheo, outside, every night that it was held in a non-accessible space. After a few mentions of this, Baraka politely pointed out, “you’re the only person I hear calling for that.” It might be a strong a statement, but the people who would experience the most hardship and discomfort in repeating the “Open Non-Mic” would be exactly the people the action is intended to support. For the people using wheelchairs particularly, it would mean paying for transportation to the venue, staying out on the street the whole time, and exhausting themselves unnecessarily. In other words, being an ally means listening to the needs of the stakeholders, rather than imposing one’s own solutions. The Working Group, instead, chose to boycott inaccessible spaces.

What are the ROOTS values — cultural organizing, dialogue and facilitation values — that we enacted in that moment?

- Stay in the room. Or stay on the street, in this case; stay in the moment of challenge and discomfort. Don’t just leave, commit to working through it together.

- Hold Space. Create a container. People will fill it.

- Be an Ally. Ask the stakeholders what they need from allies. Give up some privilege.

- Be an Artist. Contribute your artistic skills in service of the intervention, not just as the entertainment, but as a catalyst and support for the organizing, an enactment of vision.

The “Performing Disability / Enabling Performance” Working Group did a tremendous job of raising awareness, strategizing, and articulating demands for future Encuentros. They modeled cultural organizing excellently. Before the end of the Encuentro, they had staged another intervention at Concordia University, organized a “Long Table” dialogue in Lois Weaver’s “Library of Performing Rights,” and presented a list of demands before the full conference, which were publicly accepted by the Founding Director of the Hemispheric Institute, Diana Taylor. The group will continue to work together, with Hemi, toward greater accessibility at the next Encuentro in Chile, 2016.

The Statement of recommendations crafted by the Working Group can be found here.

Intervention 2: The Ethics of Humor, and Staying in the Conversation

On the third day of the Encuentro, celebrated theatre artist and Mexican activist of epic proportions, Jesusa Rodriguez, performed a new work titled Juana la Larga. Based on research into an actual case of an intersex person who faced the Inquisition in Guatemala in 1803, the performance utilized Jesusa Rodriguez and Liliana Felipe’s infamous aesthetics of parody, political satire, and cabaret. However, two enormous conflicts arose in response to the performance, both centering on issues of representation in relation to comedy: (1) a characterization of a Japanese doctor through stereotypical gestures (slanted eyes and buck teeth) that were viewed as racist, and came to be referred to as an instance of “Yellow Face” and (2) the representation of transgendered or intersex bodies, specifically through inanimate objects — predominantly a medical mannequin — by cis-gendered artists. The latter was summarized by Encuentro participant Dan Fishback, (who prefaced his comment by stating that it’s his personal point of view only):

“The corpse of a gender non-conforming body (a woman who appears to have a penis), who was not given a voice/subjectivity, plus various jokes making fun of her anatomy, in the context of a world where trans women are regularly murdered and then mocked in public, added up to a show that felt dismissive of the very people it wished to champion.”

Rather than go into the details of the arguments here, I intend to focus on the process by which the conflict unfolded. The first semi-public communication that a controversy was brewing appeared on Facebook and Twitter feeds. By the following evening, when Jesusa was scheduled to host the Transnocheo, Hemispheric Institute leaders decided to have a Town Hall to address the issue. Diana Taylor was on stage as the moderator, with Jesusa and Liliana. They did not seem to be aware, however, that several of the trans-identified artists were still returning from another action, performing a “Scream Choir” in front of the Basilica in Old Montreal. A small group had also been working on a written statement, which (I was informed by text message) was speeding toward the venue in a taxi while the Town Hall was in progress. Because there had been no public space for airing concerns previously, and there was no impartial facilitator in place, it became an unruly scene with an array of critiques ranging from inaccessibility, to anti-Asian racist imagery, to transphobia. Multiple issues were playing out at the same time, each interrupting the resolution of the other, while the power dynamics of the academy were very present in the space, but wholly unacknowledged. People were not able to hear each other. Further (and we experience this issue all too often at ROOTS Week), there was an urgency imposed by the pressure to get back to the schedule. Needless to say, it was not a very productive forum.

So, to Hemi’s credit, they tried again. Word went out that there would be a Long Table dialogue with the artists on Thursday, at the Library of Performing Rights, on the topic of “Representing Bodies and Experiences.” The room was packed. There were cameras and microphones. What some stakeholders expected to be a more intimate dialogue once again became a public spectacle, complete with a performance intervention by the Performing Asian / Americas: Converging Movements Working Group, featuring a “Yellow Face” Fashion Show, paraded atop the Long Table.

To watch the video archive of the entire Long Table discussion, “Representing Bodies and Experiences,” click here.

Now, the Long Table, as designed by Lois Weaver, has a structure and guidelines that can be very useful for self-facilitating dialogue. You can only speak when you’re seated at the Long Table, which means that others must listen until a place at the table is open. But again, by design, there was no facilitator and the power dynamics in the room were unmediated. And again, many people left feeling deeply unsatisfied, if not disillusioned. For some, as one trans-identified artist commented afterward, the tensions in the room raised “the pain of feeling excluded by communities we once called our own.”

By this point, however, Jesusa had posed a very important question. She said she wanted to better understand the Ethics of Humor — which I believe is precisely the right question. She said, in the first Town Hall: (my rough translation/paraphrase) “I’ve spent my entire career trying to offend people, but I want to offend the right people — the oppressors, not the ones who’ve already been victimized or marginalized.” No one was suggesting that humor or parody itself should ever be censored, or considered off-limits to the activist artist. Instead the challenge was to understand how to treat humor ethically, with regard to who is being parodied, and what that parody actually performs (or does) in public space, in various socio-political contexts. This is less a question of intention, than of very specific aesthetic choices, or even the ways those choices are performed in the moment, on stage. This question also presupposes that an artist has a responsibility to be ethical — a value that Alternate ROOTS assumes, by virtue of our mission “to dismantle all forms of oppression” — but which I soon discovered is a belief that not everyone in the Hemi community shares.

The Long Table experience is not the end of this story, thankfully. Jesusa and five other queer and/or trans-identified artists were committed to staying in the conversation, to working through the discomfort and difficulty together. I was honored to be included in a private dialogue at the hotel, the night before Jesusa left, along with artists Tobaron Waxman, Nyx Zierhut, Dan Fishback and Susana Cook.

There was a tremendous hunger to understand, willingness to listen, generosity and openness. There was a genuine, shared interest in hearing each other, and learning how to better work in solidarity together. As Nyx Zierhut later described, there was an appreciation for “the importance of feedback and whether/where political accountability fits into our ethics of creative process,” as well as an exploration of “coalitional politics as an organizing strategy, amongst cultural workers, artist/activists, and people targeted by gender-based violence.” We were able to go deeper into a conversation about contemporary tensions between lesbian-identified and trans-identified communities, as well as the difficulties of translation (both cultural and linguistic). It was a mutual exchange of learning. Dan Fishback posted later, “Looking back, I second-guess many of my reactions in the audience, and this experience has made me more sensitive to translation and mistranslation, and more vigilant about my own Anglo-American biases … Tobaron gave [Jesusa] the names of two South American intersex activists, and I walked away feeling humbled and optimistic.”

We were able to achieve this level of discussion, share critiques, challenge each others’ readings of the performance, discuss different historical contexts, as well as issues of representation and agency — in two languages, as a small group of queer-identified folks in intimate conversation. To me, this was a true encuentro.

I experienced the hotel dialogue as a very productive, and very safe space (in the sense described at the beginning of this article), in a way that the spectacles created by the Town Hall and the Long Table did not ultimately support. I believe those spaces could have supported large-group dialogue, with active facilitation to mediate the very charged power dynamics in the room, and some intentional structures in place to support collective work. For example, it’s notable that the “Performing Disabilities” and “Performing Asian / American” Working Groups were able to organize responses, articulate needs, and take action, because they had working groups already in place; whereas the trans community did not. This could be a recommendation for future Encuentros.

When I reflect on ROOTS values that we work toward, have been challenged by, and that can be helpful in these difficult dialogues, I think of the following:

- Assume Responsibility. Be accountable for your words, gestures, and actions. Investigate the ethics of your work. Care about the realities of trauma, whether you understand their origins or not; endeavor to listen and support.

- Organize with Stakeholders. Communicate directly with the people most affected by the issue, before making decisions. Support structures in which organizing can happen.

- Value Facilitation. It’s a strong field of practice, with skill sets that can be useful in making difficult public dialogues productive and gratifying.

- Release the Oppressions of Time. Recognize that prioritizing “time management” and “the agenda” over the issue that has organically arisen from the body is a classic way that systemic racism, patriarchy, and other forms of hegemony manifest. Consider prioritizing and honoring human experience, and the expressed needs of the group. And roll with it.

Intervention 3: I AM / NOT Enamored (a durational performance)

On the afternoon of day five, in between the Long Table and the small group discussion with Jesusa, I went to see a performance. I had heard queer colleagues expressing excitement about seeing Nao Bustamante’s Silver & Gold, and though I hadn’t read the description in advance, I decided to attend, despite the emotional exhaustion that was setting in. Honestly, I was hoping to be entertained.

Instead, I was shocked — not by the excessive penis imagery which she warned us of before the piece began, nor the gender-bending, nor the diva persona. I was shocked by the completely unchecked, unapologetic, seemingly unaware, straight-up Orientalism of the performance. It began with a female figure completely covered in a black veil, which was soon (after the penis movie), removed to reveal a sexy femme-fatale character beneath, wearing sequins and a strange headdress …

Pardon? What is “Orientalism,” you ask? The academic answer is that it’s a complex theoretical framework first articulated in 1978 by the late Edward Said, acclaimed public intellectual who wrote extensively about culture, the media, exile, politics affecting the Middle East, and Palestine. A more direct answer is that it’s a form of racism, specifically which depicts North African, Middle Eastern, and Asian cultures (formerly called “Oriental” by colonialists, and still referred to this way in most of Europe) through a stock set of stereotypes that continue to be recycled, repeated, reiterated, imitated, and cited as if they were “real” by Western producers of culture — from scholars, to anthropologists and historians, to artists, to newscasters, to religious leaders. These stereotypes, images and tropes are familiar — you know them when you hear them. And you either believe in them, or you see the racism of them …

Or, perhaps, you enjoy them, as this performance asked us to do. The show, which mixed short videos with live performance, was billed as a :“‘filmformance’ that evokes the muse of legendary filmmaker Jack Smith and his tribute to 1940s Dominican movie starlet Maria Montez in a magical and joyfully twisted exploration of race, glamour, sexuality, and the silver screen … Honing-in on Smith’s interest in Hollywood’s obsession with the reproduction of the exotic, Bustamante will embody Miss Montez.” So you might allow yourself to be entertained, and say the “exotic” is fun and exciting, maybe even sexy, or retro … and hey, if it’s queer camp, anything goes! Or, you might intellectually justify it, because after all, a famous scholar wrote about this work, and it was a reference to the work of a famous filmmaker, and yet another famous film star of the 1940s, and …

Wait a minute … Ummm … I would really hope that most of us, in 2014, might think twice about performing, say, 1940s Hollywood images of Blackness on stage — even if it was an homage to an actress, even if it was meant to be “campy” and cute. Most of us would understand, pretty much immediately, why that would be very problematic. So why would this highly educated audience of scholars, activists, and artists, suddenly feel that it’s OK to perform 1940s Hollywood images of Arabness? Hadn’t we just spent two days collectively responding to a 30-second image of “YellowFace” in Jesusa’s show? Hadn’t we talked the entire morning about the violence of reiteration? What makes it still permissible, in 2014, to perform stereotypes of Arabs, North Africans, Sheikhs, Muslims, and especially “exotic” images of “Middle Eastern” women? What made it permissible for this audience to laugh?

Orientalism. It’s so prevalent, everywhere, that it seems normal. “Orientalism,” Edward Said writes, “is after all a system for citing works and authors.” Camp is no exception, and queering an Orientalist fantasy does not change the fact that it reiterates (repeats or reproduces) racist imagery. It’s precisely the reproduction of the “exotic” that feeds anti-Arab racism today. As Said pointed out, “the connection between imperial politics and culture is astonishingly direct.” In a time of actual war, and violent racism targeting Arab, Middle Eastern, Western and Central Asian people (along with anyone who looks Arab), we must ask ourselves — especially as artists living in the United States — whether we are contributing to an imperialist history and systems of cultural production, or really working to dismantle and subvert them. Reiteration alone does not achieve subversion. Reiteration embodies and reproduces historical violence. Performing, or even just allowing and excusing, the re-production of stereotypes on-stage enables the violence to continue. “My argument,” Said writes, “is that history is made by men and women, just as it can also be unmade and rewritten, always with various silence and elisions, always with shapes imposed and disfigurements tolerated.”

Nao Bustamante later posted on Facebook, in response to the “controversy” about her work, that it was intended as parody, and that audience members might have become conscious of their own internalization of these tropes, and “maybe even feel ashamed that they laughed.” But my experience, as a woman-identified Arab American sitting in that audience, is that most people did not feel ashamed at all. The majority did not show any sign of discomfort, or critical self-examination. They simply enjoyed the show.

And I suddenly felt very unsafe among my colleagues. Not because I thought any harm would come to me personally, of course, but because I felt isolated and alone with my concerns. Because some white queer colleagues tried to justify the performance to me afterward, insinuating that I must be ignorant of the very savvy references it incorporated. Because the fact of U.S. military intervention and aggression, in the Middle East is something that occupies my mind daily, and I cannot be “entertained” by the racism that fuels such violence. Because I can’t “just lighten up” about it. Because the current atrocity of what’s happening in Palestine, right now as I write this, haunts me. Because I know real people, individuals I care deeply about, who are there and could be in danger. Because I too often feel powerless in the face of global military violence, and at the very least, I sometimes want to feel that I’m surrounded by people who understand. Because in my daily life, living in Florida, I am too often surrounded by people who support war and American imperialism. Because too many people still believe in these stereotypes when they see them on the so-called news, and too many people still laugh when they’re paraded on stage.

I was interested in some coordinated response, but there was no infrastructure to support organizing for it — there was no Arab/North African/Middle Eastern/Central Asian working group, for example. There were few of us there, and we mostly did not know each other. It just so happened that the “Performing Asian / Americas” working group had a meeting at the same time as the show, so none of them saw it, and did not feel equipped to respond. And in general, the Hemi community was already expressing exhaustion around controversy and loaded dialogues, with slogans emerging such as “I am not your enemy” (ironically) — as proclaimed at the closing ceremonies.

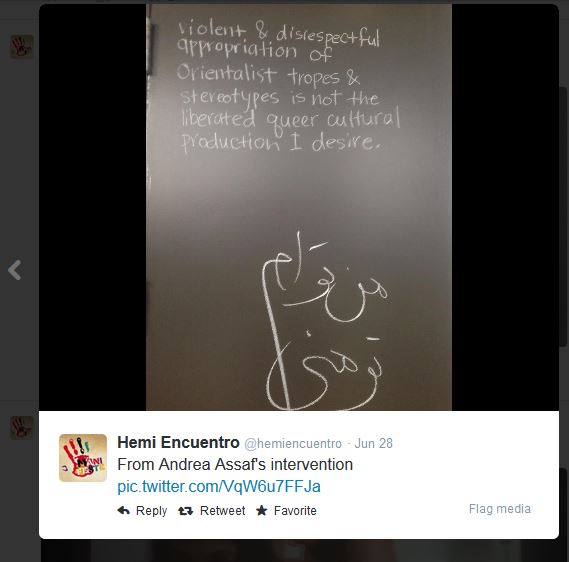

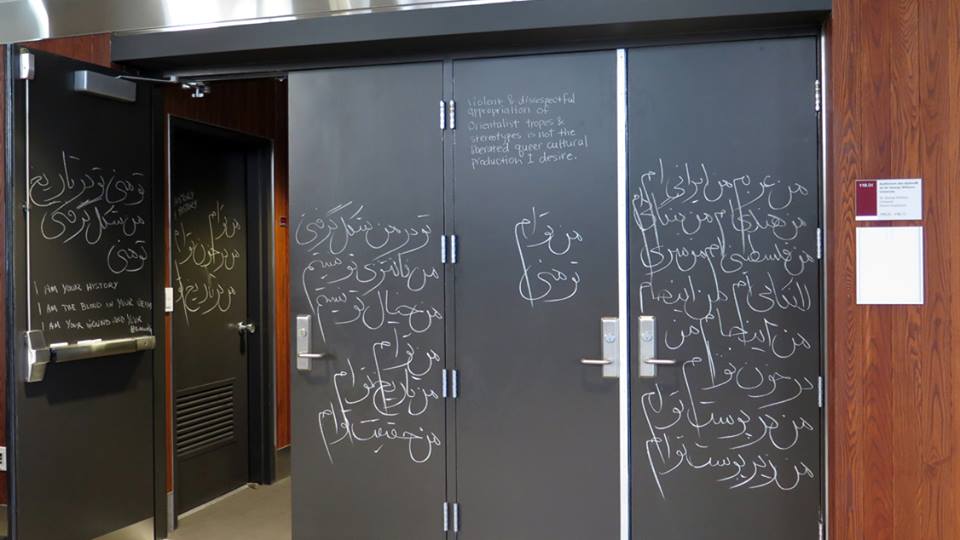

But there was a ray of light … The following day, Farsi script began appearing in chalk on the sidewalk outside of Concordia University, where Silver and Gold had been performed. Also in the audience of Silver and Gold was Iranian artist and scholar, Gita Hashemi, who is based in Montreal. We didn’t have an opportunity to speak to each other, but it was a sign … A sign that I was not alone.

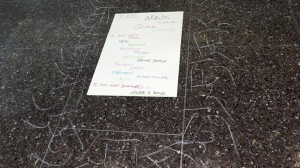

On the seventh day, the last day of the Encuentro, I decided to stage an intervention. I called on a few members of the ROOTS team for support, to hold space, and they did. I began very simply, with a text that stated my positionality, and enumerated the stereotypes that we had seen in Nao Bustamante’s performance, in exactly the order in which they appeared. It began like this:

I AM Arab

I AM American

I AM Queer

I AM Woman

But …

I AM NOT Veil

I AM NOT Bellydance

I AM NOT Sequins

I AM NOT Poison

I AM NOT Suicide

I AM NOT Femme Fatale

I AM NOT Exotic

I AM NOT Fantasy

I AM NOT Queer Fantasy

I AM NOT Merchant

I AM NOT Slave Owner

I AM NOT Rich

And …

I AM NOT Enamored

with Silver and Gold

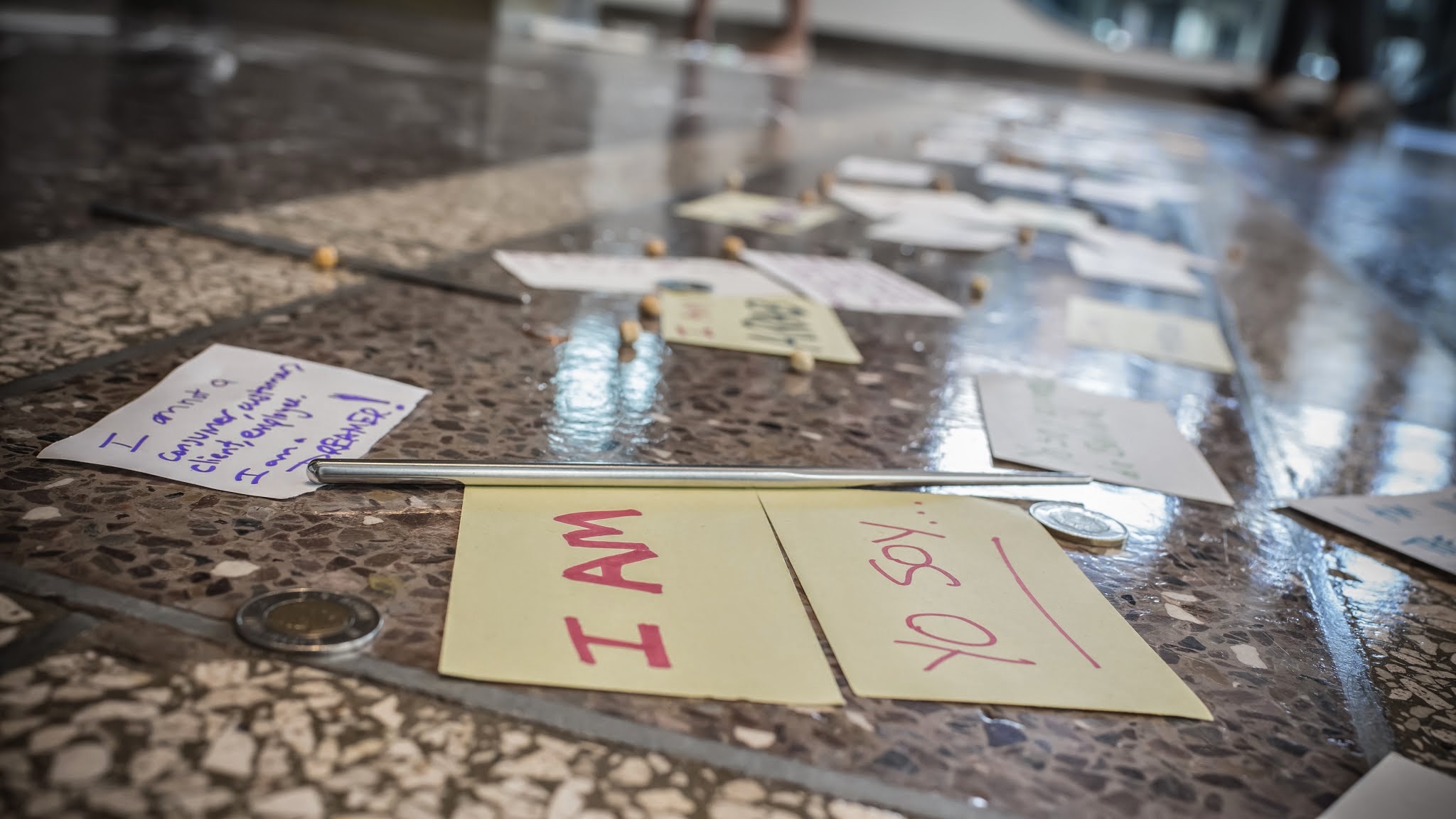

I chose a location, in the Concordia building where Encuentro participants would be passing by on their way to final Roundtables and performances. I added a soundtrack (pieces from Eleven Reflections on September) and began to evolve an improvisation structure. It started with the text above, followed by running in response to a newsreel about war, followed by repetitions of the word “reiteration” with a coin stuck in my mouth. It was a simple, repeatable structure, with room for improvisation, that invited people to participate. I had set out note cards and markers, and invited passers-by to write: Who are you? What are you not? I thought I would do this for 15 minutes, and simply repeat it in between sessions. But it became a four-hour durational performance; new audiences kept coming, and unexpected things kept happening.

Shortly after I began to perform, Gita Hashemi arrived, and joined in. She began writing with chalk — marking the space, making our presence visible — on the floor, the walls, the doors, even the plant holders. She later described the intervention, which she titled Imagined Encounters with my Other Half:

“On the last day of the Hemispheric Institute’s Encuentro at Concordia University in Montreal, amazing artist Andrea Assaf and I ended up in an impromptu collaboration. Without having talked about it, we both felt it was necessary to intervene in the dominant discourse of the Encuentro which, on the one hand absented meaningful representation from ‘Middle Eastern,’ South and West Asian cultural communities and artists, and, on the other, promoted Orientalist stereotypes in the performance Silver and Gold by Nao Busamante. As Andrea performed a response to Busamante’s work, I continued inscribing the space with a record of our presence in imagined conversation with the ‘Hemi’ … These images record my embodied writing … as well as the great overlap with Andrea’s intervention.”

Click here for more context, photos and reflections by Gita Hashemi.

As the intervention continued, others began to participate. Some artists, such as Nicole Garneau, stepped into the space and spoke about who they are, while others wrote out cards. Some also took up chalk and wrote on the Concordia floor:

i am not a metaphor.

i am not a discursive tool.

i am not your symbol.

i am not an object.

i am not a pedagogical implement.

i am not your student.

i am not a medical syndrome.

i am not your stand-in for diversity.

i am not any one identity.

– Nyx Zierhut

So what are some of the ROOTS values that we embodied on Day Seven?

- Take Action. When dialogue is no longer possible, make shit happen. Be creative.

- Collaborate. Even if it’s spontaneous. Say YES. Improvise. Support. Show up.

- Break the Silence. As the great Audre Lorde wrote, “Your silence will not protect you.” If you see or feel injustice, speak to it. Don’t wait for someone else to do it for you.

- Embody Theory. Artistic practice is an expression and embodiment of our political and theoretical concerns. This is how we do. Performance is not just a “subject” in school or an object to be studied; it’s a process for people who have been objectified historically to reclaim agency, and become subjects.

Conclusion: “Calling on Each Other’s Humanity”

After the Hemispheric Institute’s Encuentro was over, I received a call from D’Lo, the trans artist who was our spontaneous emcee at the “Open Non-Mic.” We reflected on some of the challenging moments, and how it all went down. D’Lo reminded me of what it’s really about when we “call each other out,” or challenge each other’s word choices, gestures, or actions. “We are calling on each other’s humanity,” D’Lo said. “Sometimes we forget that the politic was created to make a more just and loving world … It’s about the feeling that someone should be able to move in this world freely … to feel safe on the street … I always engage people with their responses to my work, even if it’s painful.”

Indeed, that’s one of the many things I appreciate about the Encuentro — that the Hemispheric Institute recognizes the importance of creating a space in which deep engagement with artists, about the work, is valued. They have created a space where interventions are not only possible, but encouraged! As Hemi’s Associate Director of Arts and Media, Marlène Ramírez-Cancio, posted after the Encuentro:

“In the continual spirit of what we do in and around the worlds of performance and performance studies, it goes without saying that the process of critiquing plays [an important role]. Giving artists feedback, even pushback, is essential. Otherwise, why bother to share material? Why have an Americas-wide exchange of ideas and practices? Why open up spaces for networks of artists, academics and activists to collaborate? … That’s what we’re here for.”

That’s what ROOTS is for, too. In this article, I have reflected on some of the practices, skills, and values that ROOTS has to offer in our exchanges with the Hemi community. The values I’ve articulated are not officially organizational values of Alternate ROOTS; rather they are values and practices that I have learned through the mentorship, leadership, and lived examples of other ROOTS members over the years. And ROOTS members are the ones who create what ROOTS is; just as Encuentro participants are the ones who create the Encuentro itself. We come from different arenas within this field (or perhaps overlapping fields) of performance and politics, practice and theory. Activism and art.

I am eternally grateful for the frame, the theoretical lenses, that Performance Studies has given me. Just as I am eternally grateful for the practices and values ROOTS has cultivated within me. The opportunity to connect my ROOTS life with the Hemispheric Institute is like discovering new synapses in the brain. Like finding the missing half of a whole. Like witnessing possibility in the making. Like a Bakhtinian Circle.

Maybe these two communities need each other. Certainly, we all have a lot to offer one another. Maybe, as the old Civil Rights adage goes, we are the ones we’ve been waiting for.

This is not a conclusion, really. Rather, we hope it is just the beginning of a long partnership in process, between the Hemispheric Institute and Alternate ROOTS. We look forward to welcoming the Hemispheric Institute staff and community to our annual encuentro, ROOTS Week, in the near future — and to all the insights, reflections, theory, practices, and interventions they may bring!

___________

Andrea Assaf is a writer, performer, director and cultural organizer. She’s the founding Artistic Director of Art2Action Inc., and National Coordinator of the Institute for Directing & Ensemble Creation (Art2Action/ Pangea World Theater). She’s also a consultant with the Arts & Democracy Project, former Artistic Director of New WORLD Theater (2004-09), and former Program Associate for Animating Democracy (2001-04). She has a Masters degree in Performance Studies and a BFA in acting, both from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Andrea’s performance work ranges from interdisciplinary solo and collaborative productions, to spoken word. Original, full-length touring productions include: Outside the Circle (2012), Eleven Reflections on September (2001), Fronteras Desviadas / Deviant Borders with Mujeres en Ritual (2005-06), and Globalicities (2003). Recent directing credits include: Speed Killed My Cousin by Carpetbag Theatre (2012); breaking letter(s) by Suheir Hammad (2008); Parang Sabil by Kinding Sindaw (2007). Publications include numerous poems, articles and Civic Dialogue, Arts & Culture co-authored with Pam Korza and Barbara Schaffer Bacon (Americans for the Arts, 2005). Andrea’s service involves: Board of CAATA (Consortium of Asian American Theaters & Artists), Executive Committee of Alternate ROOTS, and International Management Committee of WPI (Women Playwrights International). She is a member of Alternate ROOTS and RAWI (Radius of Arab American Writers).