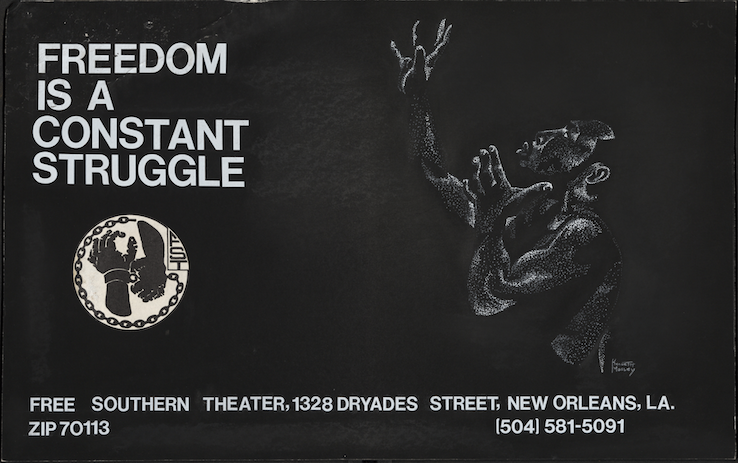

Early Free Southern Theater promotional image, circa 1970.

Jason Foster & Kiyoko McCrae (New Orleans, LA) | February 2, 2016

“Through theater, we think to open a new area of protest. One that permits the development of playwrights and actors, one that permits the growth and self-knowledge of a Negro audience, one that supplements the present struggle for freedom.”

– From The Free Southern Theater by The Free Southern Theater, 1969

Free Southern Theater (FST) was founded in 1963 during the height of the Civil Rights Movement in Jackson, Mississippi by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Field Secretaries John O’Neal and Doris Derby and student leader Gilbert Moses. They dared to try something relatively new –to tour as an integrated theater company throughout the Deep South to perform for people, many of whom had never seen live theater. FST used theater as a tool for activism and organizing. Although, the company moved to New Orleans shortly after forming, they continued to tour the South. In New Orleans they developed writing and acting programs deeply invested in the community on Dryades Street and the Desire neighborhood. In 1980, FST closed its doors and was celebrated in 1985 with A Funeral for the Free Southern Theater: A Valediction Without Mourning, featuring a jazz funeral and a three-day conference of art for social change, marking the end of an era, not only for FST but also the Civil Rights Movement. Out of its ashes, Junebug Productions was born, carrying on the legacy of theater for social change, rooted in African American traditions and storytelling.

Junebug Productions is working to honor its past by documenting the history and legacy of FST. It is important to honor where its values come from. Junebug, like FST believes that artists are important agents for social change and that amplifying the Black aesthetic by telling our own stories can help to shift power. In the fall of 2012 I was approached by Kiyoko McCrae, Junebug’s Managing Director, about a potential artistic collaboration with my company, FosterBear Films, to document FST and Junebug’s history. Kiyoko and I sat down for coffee and she began to tell me about John O’Neal, Free Southern Theater and of course, Junebug. As she was explaining what Free Southern Theater was and what they were about – the contributions that John and his colleagues made to Black theater and the Civil Rights Movement, and theater as a whole – it was as if she suddenly turned into Morpheus from The Matrix and gave me the red pill. I wanted to go further down the rabbit hole and learn more about this theater, why they came together, what their mission was, everything. A year later Junebug hosted, Talkin’ Revolution to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the founding of FST. FST members came from across the country to talk about their experiences including Dr. Doris Derby, Roscoe Orman, Jerry Ward, Chakula Cha Jua, Kalamu ya Salaam, Quo Vadis Gex Breaux, Frozine Thomas and others. It became clear that there was a great thirst for knowledge about FST’s history and the need to document its impact. Last year, we screened Free Southern Theater: Beginnings, a work-in-progress short film, at the Alternate ROOTS regional gathering in New Orleans.

Three and a half years after that initial meeting, what began as a desire to interview John for a short video has turned into a large-scale documentation project with ambitions to create a feature-length documentary about FST. The following is a conversation between filmmaker Jason Foster and film producer Kiyoko McCrae.

Kiyoko McCrae: What initially drew you to FST?

Jason Foster: I think what got me interested in it was to learn about something I never heard of before and it was basically in my backyard, New Orleans being my backyard. Being a semi-serious student of the Civil Rights Movement it was interesting to know about this whole different history that was kind of sandwiched in between these other big figures. You always hear about the MLKs, and the Malcom Xs and the Stokely Carmichaels, but, you know, this organization went on for twenty plus years and not once did I ever hear any mention of FST or a theater group doing the things that they were doing. You hear about the Freedom Rides and the Freedom Singers and even seeing the photography and videos of the Black Panther Party but you never heard about live theater.

KM: The first time I heard about FST was in a class that I took at NYU taught by Jan Cohen-Cruz, that was the first time I heard of John O’Neal and the story circle process.

Up until that point I had a pretty limited idea of what theater could be, what theater was, and hearing about John O’Neal and Junebug and FST opened my eyes to a whole other way of thinking about theater, how it could be used to create social change, and it got me interested in this whole segment of theater that I never knew existed before. It was inspiring because I’d always had this activist streak in me and I was into theater but I never really thought of the two working together.

JF: I think I had that too. I don’t know why I was drawn to the Civil Rights Movement. It was probably because I lived in the South most of my life. Everywhere you turn there is a reminder of segregation. So yeah, I think it was just a curiosity, what was this group about? When we finally sat down with John in the fall of 2012, basically spending a day with him and hearing all of his stories, it was like discovering a whole new world within the world that I already thought I knew.

KM: The world that you thought you knew, meaning the Civil Rights Movement?

JF: Yeah and the world that is always fed to us every February it just kind of becomes white noise. You hear that same thing mentioned over and over.

KM: So what do you remember about that day the most?

JF: The one thing I remember the most was probably the story circle and that whole process.

KM: What was it about the story circle?

Read an article by John O’Neal on the story circle process here.

JF: Equal time for everybody and everybody had to be quiet which is a very hard thing to do.

KM: We’re not used to conversing or sharing in that way.

JF: No. But it’s very child-like in the best way possible because that’s how kindergartens and elementary are taught: “be quiet,” “share,” “respect others.”

KM: Maybe it’s about stripping away the ego. And John, in that interview (2012), talked about first developing the story circle process with the audiences that came to see FST plays and I always wonder what that would have been like for the audience to be asked to share their stories and what their stories would have been like.

JF: Being the rural South, I think those stories would have been the range of all emotions – angry, happy, funny, sad. Whatever they said would have probably been dictated by what they just saw.

KM: John also talked about some of those stories they heard from the audiences as being the inspiration for the Junebug Jabbo Jones character. I always found that really interesting, that this character is an amalgamation of all these stories and the wisdom of everyday people, which is what I think of when I think of the Civil Rights Movement. It’s the wisdom of everyday people who are the actual heroes of the Civil Rights Movement.

JF: These leaders didn’t just come out of nowhere and it truly was a grassroots movement, and it was the people behind them that lifted them up. The leaders were the vessels of the people that they were talking for, trying to fight for their rights.

KM: It’s now 2016, almost four years after we started this project. It feels like the more we work on this there are more unknowns and there are so many more people to interview and more stories to gather.

JF: Obviously we are further than we were four years ago but it’s one of those things – the more you know, the more you don’t know – and with a history as rich as FST with almost twenty years of ups and downs they went through as a company going from integrated to all Black and the waves that caused with the white counterparts who understood it but still wanted to be a part of it because they were there longer than others. So with that and everything else that we had been learning it organically became, “maybe we should make a feature.”

KM: I remember we were trying to get the edit done for A Conversation with John O’Neal, the first documentary, and Kalamu ya Salaam said, “You have to interview Doris Derby. You can’t finish that without talking to her,” and so we made that trip to Atlanta and that was in March 2013. Meeting her opened up a whole other perspective on the founding of the theater and it was really interesting to hear her perspective on why they choose theater and how theater could encompass all these different art forms and of course her commitment to Jackson and staying there when the company moved to New Orleans. She felt it was really important to stay there and continue doing the work she had started there.

Read an interview with Doris Derby here.

JF: So when you have history that deep it’s like where do you focus, you know? And then when there really isn’t film footage of them doing the plays, you want to see it, if you can. We have photos but when you read about them performing in open fields or churches or cotton fields, that’s striking imagery.

KM: For sure, but you know as we’re talking I had this new idea, this thought that maybe the power of their work is in the stories that people tell about how FST impacted them? We just need to find more people who saw the company, saw the plays or who were a part of the company. It would interesting to put out a call in New Orleans…

JF: New Orleans, Mississippi, Alabama…

KM: I feel like every time I talk to somebody who saw an FST play their face just lights up. Like you said, it was something special that people have real fond memories of.

JF: To see people – even now – to see people who look like you on stage playing these powerful roles, not always playing a subservient role, you know, that has to be special. That has to give you power. Even if it is a play, just that image of seeing a Black man or a Black woman, you know, who might look like your mom or dad or look like you – being treated as an equal. When you see somebody like you doing something powerful and in a good way and not a hateful way, it’s inspiring.

KM: I’ve also heard John talk about the white actors playing the role of these white oppressors and the audience actually having the power to “boo” those characters or talk back and critique or comment, that must’ve been powerful too, to play out those emotions, feelings that weren’t allowed in that society.

JF: It’s cathartic. If you live in a city where you’re looked at as a second-class citizen and if you can go to the theater and not feel that way for two hours or however long or if you’re going to the writing or acting workshops and you can get that jolt of empowerment and enlightenment, that goes a long way. That’s part of the activism, that’s part of the organizing. It might not be organizing in the sense of “We’re going to go out and picket,” but you’re still organizing people to feel good about themselves and giving them tools to write or act or build sets. To give them the wherewithal to say to themselves “I matter too and I can contribute even though I’m Black and society tells me I can’t do anything because I’m not white.”

KM: So moving forward, working towards creating a feature length documentary, what are some ideas that you have as a director, the vision for this film?

JF: I have a lot of ideas (laughs). I’d like to go back to the towns that they toured and speak to the people who saw the plays or who had participated in a workshop and even those who felt threatened by it. With FST being as radical as it was, I want to talk those white people who harassed the company and audiences and ask them, “What had you heard about FST? What did you think was going to happen?” Did you think it was going to be like a Nat Turner revolt once they saw this?

KM: (Laughs)

JF: Which I think some people did! “These out-of-towners are going to come in here and rile up the black folk!”

KM: I think one thing that we both want to do is make sure that young people can connect to it so it doesn’t feel like an educational documentary. Without spoon-feeding people it would be nice for people to make the connections between the Black Lives Matter movement and Civil Rights Movement

JF: I think if we do it right and choose the right plays we might not even have to make that connection; it’ll be there. That’s the appeal of FST, it’s theater, you can be a little more nuanced with it, you can take chances with how you show what they did.

KM: There was a lot of poetry that came out of FST and it would be really interesting to have sections of the documentary where you hear the poetry and you see b-roll of rural countryside, the Desire neighborhood, the streets of New Orleans, images that inspired these poems. Using the film as an artistic forum to tell that story, as opposed to film as historical account.

JF: Definitely, to really put the artistry in the film and not make it encyclopedic. Of course I want to hear from John and Doris and Roscoe and Denise and other people involved. But I don’t think this documentary should be a purely talking head documentary. If we’re talking about theater and we don’t show somebody doing a monologue or a scene then what the hell are we doing? It’s called Free Southern Theater we gotta show something.

KM: I think the key is to figure out a way to convey what it was like to be on stage, to be an audience member, what it was like to witness this revolutionary theater company.

JF: Yeah, that must’ve been a hell of a thing to see.

…..

What follows is a partial treatment for the feature length documentary Free Southern Theater (working title):

We open on a cotton field. The sun is setting and the grass is gleaming with an orange burnt hue. There’s a slight wind moving through the leaves on a lonely tree, a tree that was perhaps used once as favorite picnic spot for a family or two young lovers, or a meeting place for local kids, or the site of the lynching of Black folks. But today this tree is being used as a backdrop for the Free Southern Theater during their first tour. They arrived in Ruleville, MS last night from Mileston, MS to perform Martin Duberman’s In White America.

Fading in over the scene of the field, we hear an excerpt from Elizabeth Sutherland’s article in The Nation published in 1964, describing the performance:

“You are the actors,” said John O’Neal, one of the founders of the Free Southern Theater, to the largely Negro, largely youthful audience sitting on folding chairs, benches, cots and the ground, behind a small frame house in Ruleville, Miss. They were waiting to see what was, for probably all of them, their first live play. The “stage” was the back porch; there was no curtain, and the lights hadn’t been necessary because it was mid-afternoon. Down the road, a few feet from the house, came a pickup truck with a policeman at the wheel, and a large German police dog standing stiff and ominous in the back.

…..

Jason Foster, born in Kingston, Jamaica, moved to the US when he was six, moving from state to state, primarily in the South. His nomadic lifestyle has contributed to his ability to tell stories and connect with people from all walks of life. In 2011, he co-founded FosterBear Films and has produced, directed, edited and shot more than 20 short films, documentaries, and music videos. He has also taught film classes through the New Orleans Video Access Center and Kids Rethink New Orleans.

Jason Foster, born in Kingston, Jamaica, moved to the US when he was six, moving from state to state, primarily in the South. His nomadic lifestyle has contributed to his ability to tell stories and connect with people from all walks of life. In 2011, he co-founded FosterBear Films and has produced, directed, edited and shot more than 20 short films, documentaries, and music videos. He has also taught film classes through the New Orleans Video Access Center and Kids Rethink New Orleans.

Kiyoko McCrae, Managing Director of Junebug Productions received her BFA in Theatre Arts from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts where she studied with Jan Cohen-Cruz. McCrae has produced and directed numerous theater productions including Lockdown (2013) and Gomela/to return (2014), which received the NEFA National Theater Project award, and the short films, A Conversation with John O’Neal (2013) and Free Southern Theater: Beginnings, currently in post-production.

Kiyoko McCrae, Managing Director of Junebug Productions received her BFA in Theatre Arts from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts where she studied with Jan Cohen-Cruz. McCrae has produced and directed numerous theater productions including Lockdown (2013) and Gomela/to return (2014), which received the NEFA National Theater Project award, and the short films, A Conversation with John O’Neal (2013) and Free Southern Theater: Beginnings, currently in post-production.